|

Architectural

Analysis of the Great Pyramid.

The

architectural features of the Great pyramid offer an invaluable insight into the

builders, their methods and the process of construction.

Interior Architecture.

|

External Architecture.

Associated Architectural Features.

Conclusions |

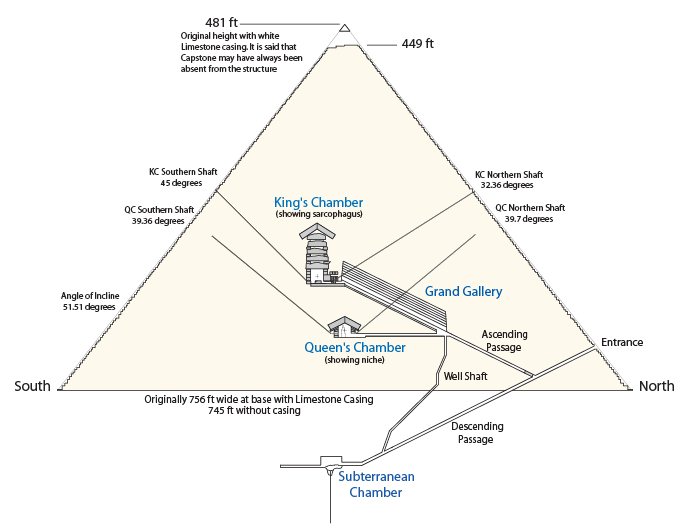

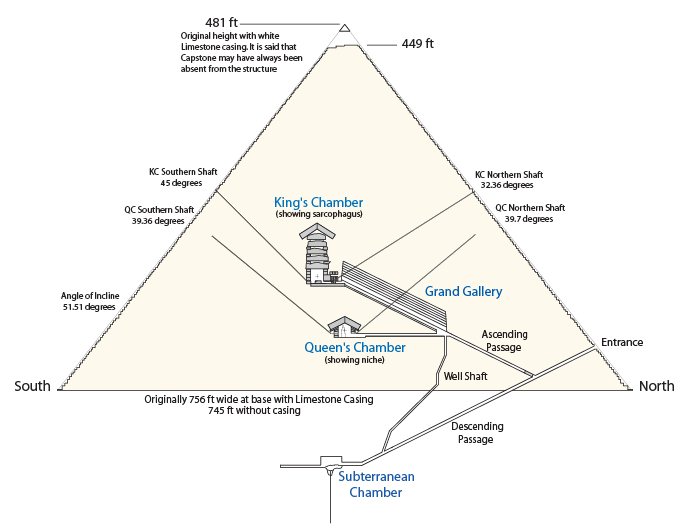

The Great Pyramid in

cross-section.

| The

Interior Features of the Great Pyramid: |

It is

understandable that so much confusion surrounds the Great Pyramid,

considering the availability of such a wealth of confusing and conflicting

facts. It is a common practice in archaeology to propose the function,

method of construction, age and builders through the design features of the

building. In the case of this pyramid however, which has been surrounded by

myth and speculation since the earliest of times, an bridge across the

border of fact and fiction has materialised, hindering the journey of

seekers of truth. This page is presented without the prejudice of previous

reports and literature, in order that the design features of the interior

speak for themselves

The following sections are laid out as if one was

entering the pyramid and travelling through its interior.

|

2.20) The

Original Entrance.

The

true entrance to the great pyramid was bypassed by Al Mamun in 820 AD. The

original entrance into the pyramid was through the

now missing door at the top of the Descending corridor, a

feature common to other early dynastly pyramids. The door

was described by Strabo around 24 BC, who said that it swivelled

open. (Text) The

true entrance to the great pyramid was bypassed by Al Mamun in 820 AD. The

original entrance into the pyramid was through the

now missing door at the top of the Descending corridor, a

feature common to other early dynastly pyramids. The door

was described by Strabo around 24 BC, who said that it swivelled

open. (Text)

It is noticeable

in Strabo's text

that he mentions

a hidden door on the south face of the pyramid, while the

door is actually on the north face.

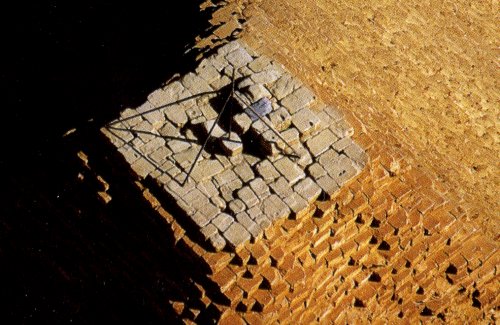

The stones that

surround the entrance are some of the largest used in the

pyramid. What we see today of course is not the entrance as it

was intended to be seen because the casing stones and masonry

surrounding it have been removed. Rather, we are able to see the

remains of what appears have been an exercise in extreme engineering.

How these huge stones and the immense corbel's relate to the final

doorway placed/hidden into an otherwise flat surface is a

mystery.

The

architecture of the entrance raises some interesting points such

as the fact that apart from the unnecessary extra work involved

in building with such huge stones or the apparent pointlessness

of having an opening door for a tomb never to be disturbed,

there is also the matter of the symbol carved over the doorway

(photo below).

Apart from

being a curious choice of location, there is little if no

agreement on what its meaning might be. The vague similarity to

the Egyptian hieroglyph for the word 'Horizon' has led to the

suggestion that this symbol might be a representation of that

word.

"According to Walter

Marshall Adams, the triangle was meant to symbolize the 'door of the

horizon', the hieroglyphic sign for the horizon�having been carved inside

the triangle, which from a distance, assumes the form of a pupil. Thus,

Adams believes, the hieroglyphic sign must be the pyramids divine name".

(16)

(More

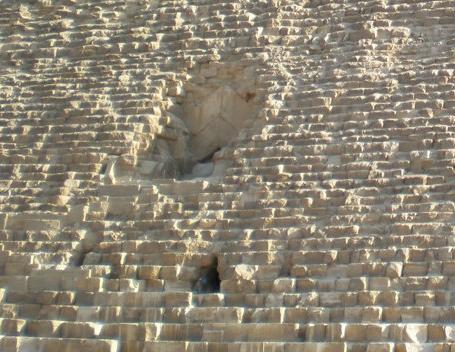

about the Original Doorway) Al Mamun's Forced

Entrance.

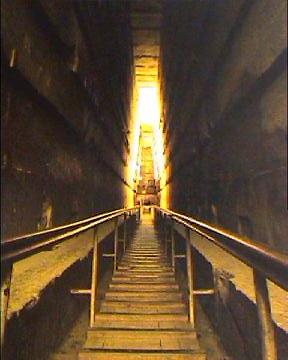

Today tourists enter the Great

Pyramid via the 'Robbers' tunnel dug by workmen employed by

Caliph al-Ma'mun around AD 820. The tunnel was cut straight through the masonry of the pyramid for approximately

27 metres (89 ft), then turns sharply left to encounter the

blocking 'plugs' in the Ascending Passage. The workmen

tunnelled up beside them through the softer limestone of the

Pyramid until they reached the Ascending Passage.

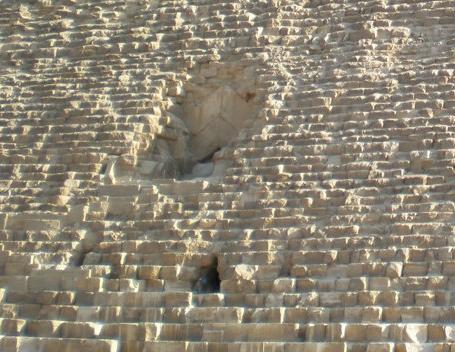

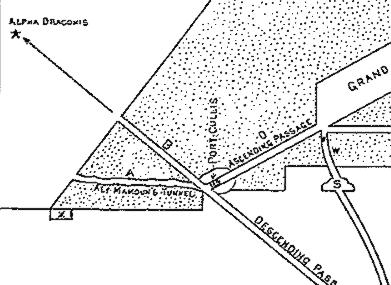

Al Mamun

decided to bore direct centre on the North face of the

pyramid and on the level of the 7th course. The

original entrance is ten courses higher and 24 feet

east of the main axis than Al Mamun dug.

The fact is that Al Mamun

appears to have tunnelled directly towards the junction of

the ascending and descending passages. The hole that he quarried was

unnervingly accurate... ?

|

|

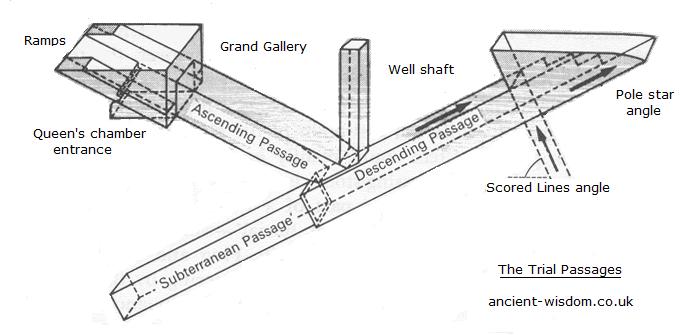

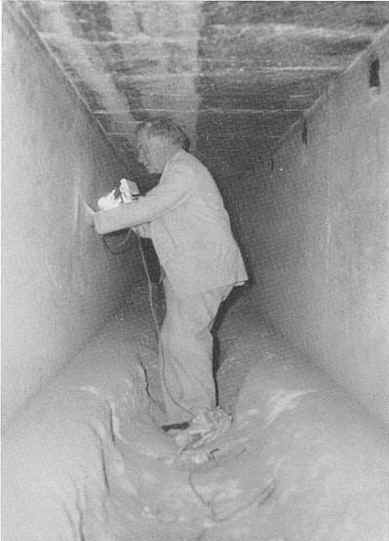

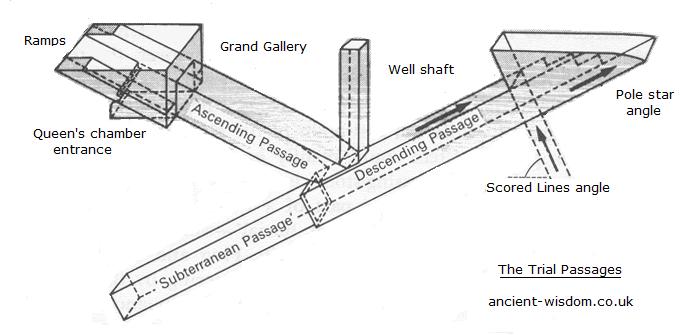

2.21)

The Granite 'Plugs'. 2.21)

The Granite 'Plugs'.

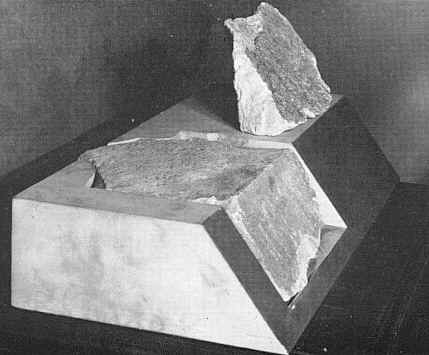

The three granite 'plugs'

which sit in

the bottom of the ascending passage are believed to have been built

'in-situ' by some sources and 'slid' into place by others.

Although other

pyramids also show evidence of having had 'plugging' stones, those at Giza

are the only ones that can still be seen today.

The ascending passage tapers inwards slightly at the bottom

end (as seen in the 'Trial passages' outside) which

would have required extremely accurately cut blocks. The granite blocks fit

almost seamlessly into the passage, barring a 4 inch cavity between the

bottom block and the next one up reported by Petrie

(13).

This has now closed, not unsurprisingly (considering one of the tapered

sides is now exposed).

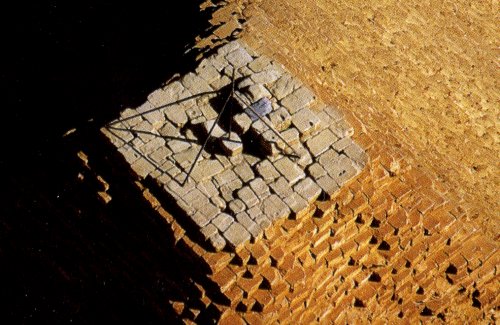

(Right: The bottom granite plug as seen from underneath)

The following testimonies describe the plugs when they were

first found. They reveal much about the design of the plugs.

Extract from Petrie: - 'The present top one is not the

original end; it is roughly broken, and there is a bit of granite still

cemented to the floor some way farther south of it. From appearances there I

estimated that originally the plug was 24 inches beyond its present end'

(13)

Extract from Petrie :-

'The broken end of the upper block, and

a chip of granite still

remaining cemented to the floor of the passage a little above that, showing

that it was probably 24 inches longer than it is now, judging by marks on

the passage. Thus the total length of plug-blocks would be about 203 inches,

or very probably 206 inches, or 10 cubits, like so many lengths marked out

in that passage.....the plug-blocks cannot have stood in any place except on

the sloping floor of the gallery'.

Extract from the Edgar

Brothers :- (Vol II) - 'The Granite plug is

composed of three blocks of red granite. There is a space of a few inches

between the lowermost and middle blocks (Petrie says 4 inches). The top end

of the uppermost block is much fractured in appearance�Professor Petrie says

he saw a bit of granite still cemented to the floor two feet further up the

passage. We, also, saw what for some time we took to be a piece of granite

at the place indicated; but on more careful examination it proved to be

a lump of

coarse red plaster. We saw several similar pieces of plaster adhering to the

angles of the floor and walls throughout the length of the passage, and we

required to clear some of them away as they hindered careful measuring. We

also saw at least one such piece of plaster in the Grand Gallery. This

coarse red, or, rather, pink plaster was very extensively used by the

ancient workmen in the core masonry of the building, and some of it can be

seen in certain wide joints in the dilapidated portion of the First

Ascending Passage. We believe that the upper end of the Granite Plug is in

its original state, and that its rough unfinished appearance has symbolic

significance. The upper end of the lowermost block also has a fractured

appearance, which is certainly original, for the stone is very inaccessible

and there is no room for anyone to work at it'.

Although

there has never been a

suggestion that the plugs were actually cemented in place themselves, this

and the (now closed) cavity between the top plugs suggest that the plugs

could have been slid into place. Petrie however, says that he found 'a

chip of granite still

cemented to the floor' in the

corridor above them.

The

Edgar brothers say they found what '...Proved to be a lump of coarse red

plaster'. Either way, if the plugs were slid into place from where do

these lumps of plaster originate? This is clear evidence that either the

plugs were not slid into place, or that some construction work

took place after the pyramid had closed, both of which demand an

explanation. Although

there has never been a

suggestion that the plugs were actually cemented in place themselves, this

and the (now closed) cavity between the top plugs suggest that the plugs

could have been slid into place. Petrie however, says that he found 'a

chip of granite still

cemented to the floor' in the

corridor above them.

The

Edgar brothers say they found what '...Proved to be a lump of coarse red

plaster'. Either way, if the plugs were slid into place from where do

these lumps of plaster originate? This is clear evidence that either the

plugs were not slid into place, or that some construction work

took place after the pyramid had closed, both of which demand an

explanation.

It has been suggested that masons

gained entry after the pyramid was closed to cut the Davison channel and

repair the damaged beams of the Kings chamber, perhaps this can explain the

origin of the plaster and rubble piled up above the granite plugs.

Although it is seems quite unlikely that masons would have re-entered a 'tomb'

for repairs after it was closed, there is evidence of repair work in

the breaching of Davison's chamber and the use of plaster for repairs in the

Kings chamber. However, unless this work was done after the plugs were slid into

place we still have no explanation for the lumps

of plaster on the floors and walls of the descending passage.

One has to ask what would motivate anyone to force entry into

a sealed pyramid just to repair it?

The repairs in the King's

chamber are associated with the Davison's chamber which was cut through existing masonry

(already completed),

if the

repair work was done before the pyramid was closed the rubble

would have been taken outside, but how does that information tie in with the

'Pyramids as tomb's' theory.

Because there is no precedent (or logic) for the argument that workers would

break back into an already finished pyramid in order to carry out 'repairs',

we are left either to conclude either that the works were so uniquely

important that they demanded attention, or that the repairs were carried out

before the pyramid was closed off, and the plaster on the walls and floor

remained there because the granite plugs were built in place. The rubble in

this scenario would be assumed to be from the breaching of the

Well-shaft by intruders at a later date.

The position of Al-Mamun's

tunnel makes it reasonably clear that he was specifically seeking entry to the upper parts

and the accuracy suggests that he knew that there was an alternative access to the upper

parts either bypassing the granite plugs or via the well-shaft. barring

complete coincidence, it is likely that Al Mamun had already seen the bottom

end of the granite plugs before he started digging. In addition, the evidence of a

forced-entry prior to Al-Mamun

seems likely, else one would assume Al Mamun would have

entered the upper parts through the well-shaft for which there is no record.

We can be clear that the pyramid had been breached before him.

If the granite plugs have been in place since the pyramid was

built, and as it has been shown that the 'well-shaft' was part of the

original design (with the probable exception of one 'roughly cut' part), it

seems possible that the upper parts were not just hidden to prevent an

'accidental' entry (being left incomplete so that only an 'initiate' would

be able to 'force-entry' at a later date - which they presumably did!), but

also perhaps, to prevent water damage (the 'rough-cut' section of the

well-shaft was cut through blocks). This supports the earliest Arab legends

which say that:

'The purpose of the pyramid was said to be to conceal the

literature and science held within it, well hidden from the eyes of the

initiated, and to protect them from the flood'.

Article: (Sept 2011).

Philip A. Femano, Ph.D.

Analysis of the Granite Plugs.

|

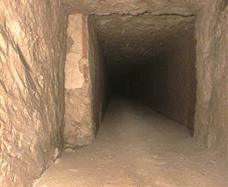

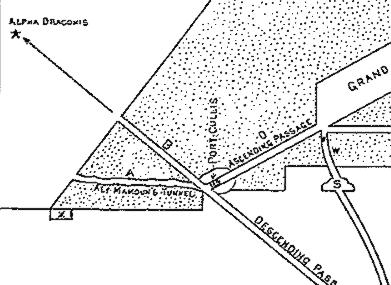

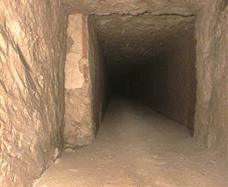

| 2.215) The

Descending Passage.

The

testimony by Strabo of a swivel door combined with the

hidden upper parts suggests that the only part of the

internal structure which were intended to be seen was the

descending passage and the subterranean chamber. The

testimony by Strabo of a swivel door combined with the

hidden upper parts suggests that the only part of the

internal structure which were intended to be seen was the

descending passage and the subterranean chamber.

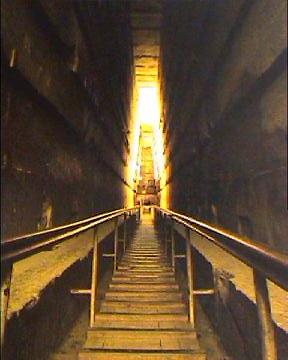

The

descending corridor extends down into the heart of the

pyramid for 91m. The accuracy is such that it deviates less

than 1/2 inch over its entire length. the passage was

designed, along with all the Memphite pyramids to point

directly towards the pole star.

Assuming

that the long narrow downward passage leading from the

entrance was directed towards the pole star of the pyramid

builders, we should be able to use this information to

discover the date of commencement of the pyramid.

Astronomers have shown that in the year 2,170 B.C (long

after Khufu was dead), the passage pointed to Alpha Draconis

at its lower culmination. It should be mentioned, however,

that the date named is not the only possible one. Mr.

Richard A. Proctor the astronomer, after stating that the

Pole-star was in the required position about 3,350 B.C., as

well as in 2,170 B.C., said "...Either of these would

correspond with the position of the descending passage in

the Great Pyramid; but Egyptologists tell us there can

absolutely be no doubt that the later epoch is far too

late..." He adds: 'If then we regard the slant passage as

intended to bear on the Pole-star at its sub-polar passage,

we get the date of the pyramid assigned as about 3,350 years

B.C., with a probable limit of error of not more than 200

years either way, and perhaps of only fifty years.' (This

date also agrees very suitably with the date given by

Diodorus Siculus).

(More

about the dating of the Great Pyramid) |

|

2.22)

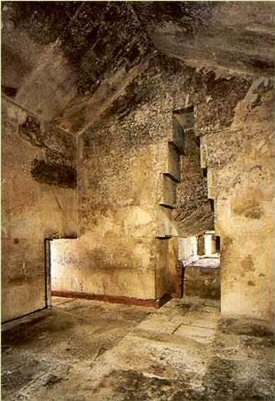

The 'Subterranean' chamber.

The first noticeable thing about the subterranean passage is that it has

the

appearance of being unfinished. The southern passage was in the process of

being carefully cut, and adds to the idea that work was stopped in the

middle of the chamber. The obvious question is - why as it was left unfinished

when it was such an obviously original feature of the pyramid. The Polar

shaft was a feature of all the other Memphite pyramids. The first noticeable thing about the subterranean passage is that it has

the

appearance of being unfinished. The southern passage was in the process of

being carefully cut, and adds to the idea that work was stopped in the

middle of the chamber. The obvious question is - why as it was left unfinished

when it was such an obviously original feature of the pyramid. The Polar

shaft was a feature of all the other Memphite pyramids.

It has been commonly argued in the past

that the upper chambers were created following a 'change in plan'. Anyone

who has actually been in the subterranean chamber will know that it would be

impossible to get a sarcophagus down there. The existence of this chamber

contradicts the 'Pyramid as Tomb' theory.

The 'pit' in the floor of this chamber

contains a granite stone with holes it it similar to the one by the main entrance, and the one

in the well-shaft. These are believed to be the 'portcullis' stones from the

King's chamber above. The pit was dug deeper by

Cavigula by another 30ft in the 1800�s.

A southern tunnel was cut for 16m leading from the

subterranean chamber. It leads nowhere, and ends abruptly.

|

|

2.225)

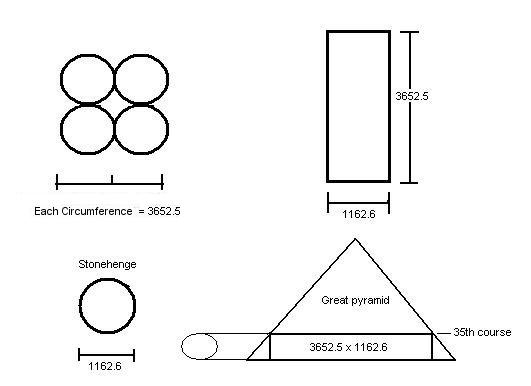

The Ascending corridor.

The bottom of the Ascending corridor was determined to have been cut

through pre-existing masonry. This has been suggested to be evidence of a possible change in design (from

the upper level where the stones were prepared).

As the descending corridor extends up to the

18th

course, we can conclude that any fitted masonry

features below that level must be from the original design. The addition of

the gable stones over the entrance bring the original hypothetical level to

around the 30th

course (There is a dramatic change in the size of blocks at the 35th

course - which

brings us to some interesting conclusions). The architectural features below

these levels include the descending passage and entrance, the girdle stones,

the well-shaft and most importantly, the Queens chamber. As it has been

shown that the lowest part of the ascending passage was cut through existing

masonry, it is impossible to say for certain whether the girdle stones or

upper passages were ever included in the first design. However, the fact

that the route to the subterranean chamber is too small for a sarcophagus

makes it likely that (at least some of) the upper parts were always intended

to be a part of the original plan.

Knowing that the lower part of the

ascending passage was cut through existing masonry, i t is at

this

level that we have to look as it was here that we can

assume the builders decided to cut a new shaft through the upper parts of

the pyramid. This does not explain how the 'girdle stones' were so

accurately included into the plan (unless they were put in place at this

time). Unless a satisfactory reason can be determined

for the reason why the lower parts were cut through existing masonry,

it is reasonable to conclude that there may have been some change in

design, although in order to accept this theory, the other

internal features need to be explained within the same context.

The top of the Ascending corridor 'meets' the top of the

Well-shaft. If the upper part of the Well-shaft is proven to be original,

then it is not unreasonable to assume that the lower, neatly cut sections

were also original. Of course, this lends weight to the idea that the upper

parts were in the original design, but still requires an explanation for the

lower section being cut (with at least one girdle-stone in situ)

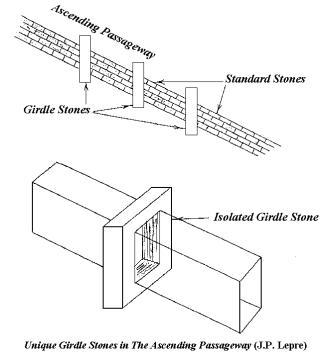

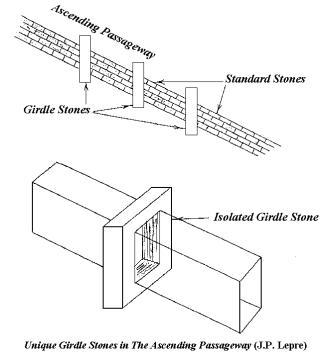

The presence of the three neatly cut Girdle-stones (below) lends weight to the original idea that the corridor (and all other

upper parts) were in fact planned from the start.

|

|

2.23)

The 'Girdle stones'.

These three stones in the Ascending corridor are baffling. They

are described in detail by the Edgar Brothers: (Vol I). who said the following

of them: These three stones in the Ascending corridor are baffling. They

are described in detail by the Edgar Brothers: (Vol I). who said the following

of them:

Extract from Edgar

Brothers, Vol I - '�The

chief discovery was, that at stated intervals the smaller blocks forming

elsewhere separately portions of the walls, floor, and ceiling of the

passage, were replaced by great transverse plates of stone, with the whole

of the passage's hollow rectangular bore cut clean through them; wherefore,

at these places, the said plates formed walls, floor, and ceiling, in one

piece�Additionally, let into the walls immediately below the three upper

Girdles, there are

peculiar inset stones, which look like

pointers�let into specifically large wall stones'�

And�' It is quite probable that the stones forming the three upper

girdles were built in entire, and the bore of the passage cut through them

in situ. The two roof stones immediately above and below each of the three

upper Girdles, are in themselves partial Girdles'.

Mendelssohn

(5)

argued that the Girdle-stones are evidence of buttress walls from an

internal step-pyramid structure. He said the following;

'Since earlier and later

stone pyramids relied on a basic core of buttress walls it is more than

likely that the same design was used in the great

Giza pyramids. Borshardt has drawn

attention to the existence of 'girdle-stones' in that part of the ascending

passage of the Khufu pyramid which was cut through already existing masonry

at the first alteration of the interior design. These are large vertical

slabs through which the new corridor passes at intervals, and he has taken

them as part of internal buttress walls',

but then he says 'This view has been

disputed by Clarke and Engelbach, who have pointed out that it would be

wholly fortuitous for the passage always to have encountered whole stones.

They also maintain, rightly, that the walls of this passage are made of

fitted stones...'

In order to reconcile this information, he concludes

that;

'...probably both sides are correct. The passage was evidently lined

with new masonry and the girdle-stones, while not being part of the original

buttress walls, were placed to mark their positions. This seems more likely

since the girdle-stones are spaced at intervals of 10 cubits (about 5m.),

which is the distance between buttress walls in the medium pyramid. This

indication of internal buttress walls shows that no novel features seem to

have been introduced in the core structure of the

Giza pyramids'.

(Other

Examples of Holed-Stones')

|

|

2.24)

The 'Queen's' Chamber. 2.24)

The 'Queen's' Chamber.

The 'Queens' chamber is

only called so because of its shape which Arab tradition ascribes to female

burials. It sits at the heart of the pyramid.

Petrie was the first to suggest that the chamber was the serdab of

the pyramid (a chamber containing a statue of the dead pharaoh.

Traces of a stairway and a table for offerings are still clearly visible on

the floor in front of the niche. Petri also notes a number of small

fragments of black stone. The serdab of Kagemni at Saqqara seems to

be a 'replica' of this chamber.

(16)

The Queens

chamber is one of the greatest mysteries of the pyramid. It's deliberate

placement in the centre of the pyramid gives it a significance which is

increased by the curious fact that it was disguised by so many numerous

hidden doorways and stone-slabs.

Having

gained entry to the upper parts of the pyramid, the most obvious place to

continue searching would have been the kings chamber as the passage to the

Queens chamber was

concealed by

a huge stone slab over the floor of the 'Grand-gallery'. Even more

significant then is the fact that the 'star-shaft's' which were perfectly

visible in the kings chamber were also 'hidden' or at least remained sealed

over, concealing two more 'star-shaft's' - which are blatantly not that at

all, as they lead only to the 50th level (the course that the 'Kings'

chamber sits on) where they are sealed off by a door made of white 'Tura'

limestone. (see 'star-shafts')

|

|

2.25)

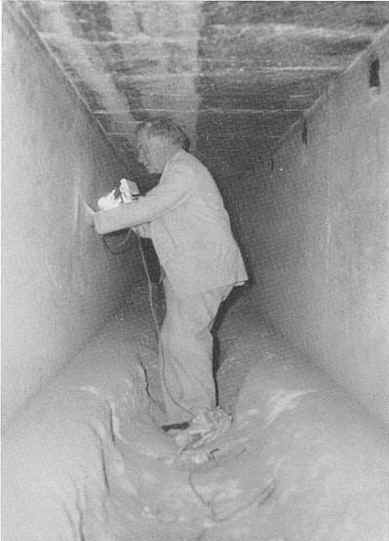

The

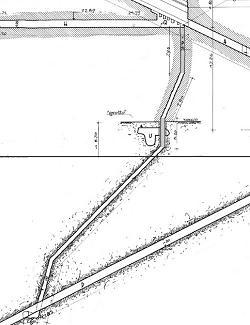

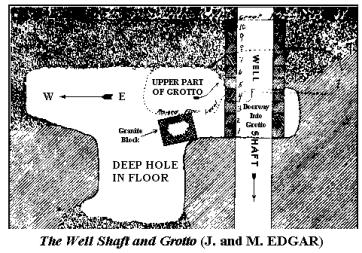

'Well-shaft'.

In the 1830's Captain G. B. Caviglia cleared the descending passage of

debris, exposing the 'pit' for the first time since the Pyramid had first

been opened by Al Mamun. At the same time, Caviglia also discovered and

opened the 'well-shaft'. Its upper opening was concealed at the point where

the horizontal passage to the Queens Chamber branches off. Clearing the

debris from the well-shaft is said to have improved the otherwise stifling

air quality in the Pit and Descending Passage.

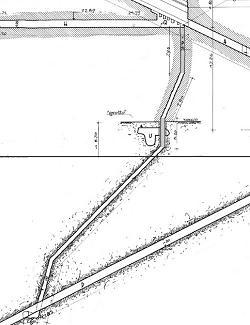

Is it possible to determine whether the well was built

before the pyramid was constructed, or after..

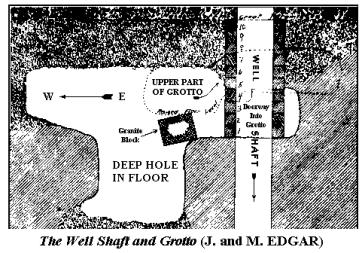

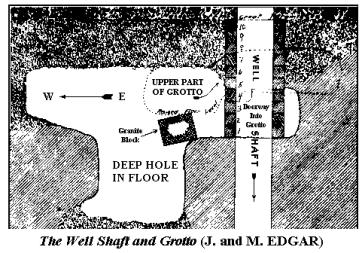

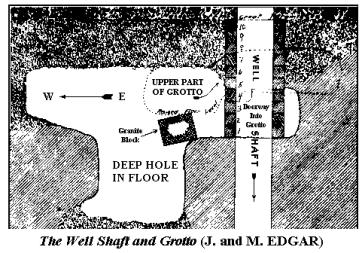

The Well-shaft lies precisely on an E-W plane parallel to the

pyramids passages and chambers. It

can be separated into seven sections, with the upper three sections passing

through 60 ft of limestone masonry and the lower segments being tunnelled

through another 150ft of natural rock. With the exception of section C which

was tunnelled through the masonry in a rough and irregular manner, and

section G, two of whose squarish sides were left rough and not quite

horizontal; all the other sections are straight, precise, carefully

finished, and uniformly angled throughout their lengths. The Edgar brothers

showed conclusively that the upper short horizontal passage, as well as

the vertical section were part of the original construction. The two

vertical sections at the top are of equal length). They also found that the lower vertical

section was built with masonry blocks as it passed through the 'Grotto'

in the bedrock. It could only have been so constructed when the rock face

was still exposed, before the grotto was covered with the masonry of the

pyramid. The Well-shaft lies precisely on an E-W plane parallel to the

pyramids passages and chambers. It

can be separated into seven sections, with the upper three sections passing

through 60 ft of limestone masonry and the lower segments being tunnelled

through another 150ft of natural rock. With the exception of section C which

was tunnelled through the masonry in a rough and irregular manner, and

section G, two of whose squarish sides were left rough and not quite

horizontal; all the other sections are straight, precise, carefully

finished, and uniformly angled throughout their lengths. The Edgar brothers

showed conclusively that the upper short horizontal passage, as well as

the vertical section were part of the original construction. The two

vertical sections at the top are of equal length). They also found that the lower vertical

section was built with masonry blocks as it passed through the 'Grotto'

in the bedrock. It could only have been so constructed when the rock face

was still exposed, before the grotto was covered with the masonry of the

pyramid.

The geometry of the shaft, the fact that the top part of the

tunnel was incorporated into the design and the bottom parts cut neatly and

correctly except for the last section, and that the upper section was cut

through solid masonry all support the idea that the well-shaft was built

(but not necessarily completed), as the pyramid was constructed.

The missing blocking stones, chisel marks around the entrance,

and the fact that a part of the well-shaft was roughly cut through existing

masonry has led many to the reasonable conclusion that the well-shaft was

breached at some time in the past in order to access the interior of the pyramid after

construction. The next question then is how was it accessed?

Extract from the Edgar Brothers (Vol II) -

The mouth of the well is formed by a portion of the ramp on

the west side having been broken away: and the appearance of the masonry

surrounding this Well-mouth suggests the thought of the once covering

ramp-stone having been violently burst out from underneath�In addition to

the breaking of the ramp-stone at the head of the well-shaft, a portion of

the lower end of the floor of the Grand Gallery appears to have been

forcibly removed.

This observation leaves the reader with the impression that

the well-shaft was cut through from the bottom up. However, the following quote creates

a different picture.

'There is incontrovertible evidence that the well Shaft is

an original feature that was dug from the top down�a close examination of

the chisel marks on the topside of the blocks that surround the upper

entranced to the shaft reveals that it was chiselled out from above'.

(10) 'There is incontrovertible evidence that the well Shaft is

an original feature that was dug from the top down�a close examination of

the chisel marks on the topside of the blocks that surround the upper

entranced to the shaft reveals that it was chiselled out from above'.

(10)

We are left with the following confusing possibility: That the shaft

was cut surreptitiously after the pyramid was finished by someone who shared

or had been passed on the knowledge of its whereabouts. The suggestion is not a new one. In fact, the

only thing that stands in its way is the chisel marks at the upper entry

which have been established to have been cut from the top. But what if the

shaft was cut from the bottom, then opened out from the top?

Extract from Great Pyramid Passages: Vol I - 'We

have taken a number of photographs and careful measurements of the lower end

of the Well, where it enters at the west wall of the Descending Passage -

See Plate X. The opening in the wall is rather broken and rough around the

edges, although the sides are, in a general way, vertical and square with

the top. Professor Flinders Petrie believes that the opening was at one time

concealed by a stone' and that 'Al Mamoun's

workmen made their way down the Well shaft from its upper end in the Grand

Gallery, and forced the concealing block of stone from its position at the

lower end'.

(14)

Comments

- It feels significant that the opening of the well-shaft is on the same

level as the 'Queens' passage and chamber. That it was blocked (built over),

for a section towards the top end during construction, but not completely to

the top, is also significant. There must have been a good reason for

concealing it and re-entering it. Yet we can assume that it was not meant to

be found easily yet probably intended for 'reasonably easy access' at a

later date.

Whoever completed the tunnelling had a plan from which to

work by in order to make the final connection and that whoever cut it was

privy to that information. 'It is also possible that the short passage that

connects the two sets of chambers in the Bent pyramid, which is clearly not

part of the original design, was also tunnelled by robbers who knew the

layout'.

(10)

Question:

It was reported that the Well-shaft was partially filled with debris when it

was found so how did the person who filled it get out?. In addition we need

to understand where the debris originated and what was the purpose of

filling it for that matter. In fact, it is worth asking if it was ever

re-sealed at the bottom end.?

Pochan

(16) manages to 'clear away' the issue of rubble at

the bottom of the tunnel. He quotes Coutelle, from the Napoleonic expedition

who recorded the following:

'While descending, I had stopped at a sort of

grotto found above the steep part of the well; that is, in the second

vertical part. This excavation had been made by removing pebbles, bits of

which still remained stuck to the arch; there were more underfoot. I rested

there (and) compared the pebbles I was carrying with these pebbles and

ascertained that

the pebbles at the bottom of the well derived from the excavation of this

grotto'.

The logic of the finding is sufficient to conclude that it is probably

right. It does, however, mean that whoever displaced the pebbles had no

intention of exiting the building via the bottom of the well-shaft.

|

|

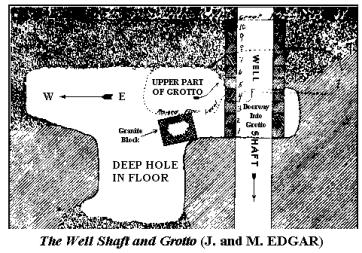

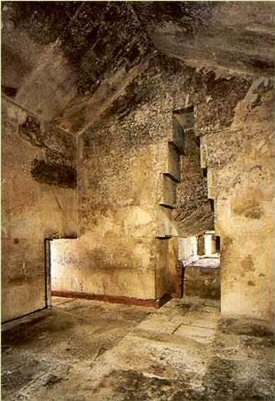

2.26)

The Grotto.

It has been reasonably suggested that the 'Grotto' may have been an original

landscape feature, and that the pyramid might have even been built over it.

However, it is the 'Queens' chamber that occupies the central position of

the pyramid, and not the grotto (although its upper entrance is on the same

level).

The block-work from the upper entrance down to the grotto has

been shown to have been laid as the pyramid rose up which points to the idea

that in some way, the area down to the grotto was an original feature. (The

same is true of the tunnelling below the grotto. It is clean and well

worked). The only rough cut passage is above the grotto, cutting through the

existing masonry until it meets the prepared passage above it.

Lepre

(10),

noted that inside the grotto: 'The ceiling is unusually damp to the point

where there is actually a perceptible coating - like a light frost - over the

pebbles themselves. This unusual composition naturally tempts one to speculate

about the existence of a nearby water source'.

It has been suggested that the grotto was built to allow the

first intruders room to work. This suggestion seems reasonable as in order to cut through the blocks above, there would need to be a

well placed workspace. We can assume that the 'Grotto' had been excavated in

the past (from the 'rubble and sand' found in the tunnel below, which is

similar in composition to that found in the grotto). The only problem

with this theory is the lack of oxygen which again suggests that the top

part of the well-shaft was opened from above and not below.

|

|

2.27)

The Grand Gallery.

One of the great mysteries about the Great Pyramid remained the apparently

incomprehensible design of the Grand Gallery, a seven levelled,

elaborate corbelled vault forming the upper half of the Ascending Passage

leading to the King's Chamber. One of the most elegantly simple, coherent,

and widely ignored theories about the Great Pyramid was the astronomer

Richard Anthony Proctor's explanation of this aspect of its design. Proctor

was inspired by a passage in the neo-Platonic philosopher Proculus's

commentary on Plato's Timaes, which mentioned that before the Great Pyramid

was completed it was used as an observatory. Based on his reading of the

account he surmised that when the Pyramid was completed to its fiftieth

course, i.e. to the level of the top of the Grand Gallery, which was also

the floor of the Kings Chamber, it would have made an excellent observatory.

He documented his theory in a book published in the late nineteenth century

titled The Great Pyramid, Observatory, Tomb and

Temple. One of the great mysteries about the Great Pyramid remained the apparently

incomprehensible design of the Grand Gallery, a seven levelled,

elaborate corbelled vault forming the upper half of the Ascending Passage

leading to the King's Chamber. One of the most elegantly simple, coherent,

and widely ignored theories about the Great Pyramid was the astronomer

Richard Anthony Proctor's explanation of this aspect of its design. Proctor

was inspired by a passage in the neo-Platonic philosopher Proculus's

commentary on Plato's Timaes, which mentioned that before the Great Pyramid

was completed it was used as an observatory. Based on his reading of the

account he surmised that when the Pyramid was completed to its fiftieth

course, i.e. to the level of the top of the Grand Gallery, which was also

the floor of the Kings Chamber, it would have made an excellent observatory.

He documented his theory in a book published in the late nineteenth century

titled The Great Pyramid, Observatory, Tomb and

Temple.

The function of the ascending passage lies hidden in the

conclusions. The design features suggest that it had a specific purpose. If

it was symbolic, then the features will have symbolic explanations. The

sockets in the sides are all roughly filled except one. Who has filled them,

or were they always filled. The corbelled roof shows remains of a slot along

its length on the 3rd instep. It appears, at first glance to have held a

false roof. The Ascending passage was 'cut through' the pyramids masonry in

the first instance, rather than constructed. So why was the limestone at

this point of a higher quality than that used in the rest of the core

masonry? (They were planned from the beginning, but not finished until

later).

There

is another feature of the Grand Gallery which is worth examining: on each side

a groove�about 7 inches high and 1 inch deep�has been cut into the third

layer of corbelling along its entire length. In addition, at the top of the

grooves there are rough chisel marks running along their entire lengths. At

first impression it seems as though these may have once housed a 'false

ceiling', an idea repeated by several people.

It has been noticed that the Gallery better is 'finished off' at the

Northern, bottom half than the 'rough' Southern top section.

In 1843 Borchardt found an impression, in the walls of the

Great Gallery (BORCHARDT, L., "Einiges zur dritten Bauperiode," Berlin

1930). He established that it was made of mortar, in which a long, round

object had originally been embedded, and later removed. He could not

determine what that object may have been, but he assumed that it had been

attached to the Gallery wall by means of the mortar.

Comment

- It has been suggested that this mark was left be a piece of cord, probably

used for some kind of measuring purposes. One was also found in one of the

'Star-shafts' but it is vertical (see left), and alone makes no sense in

terms of facilitating measurement. The Edgar Brothers reported finding a

number of plaster impressions in the ascending passages, and of having to

clean many off in order to take correct measurements.

The following is an

extract from Pochan

(16) -

'Various hypothesis, each as unlikely as the

next, have been put forward concerning these slots�.But the number of slots

should have attracted the attention of Egyptologists. Wasn't Cheops the

twenty-eighth king of

Egypt after Menes? I

propose that the twenty-eight slots twenty-eight bases for twenty-eight

facing royal statues, and that the Grand Hall is actually the gallery of

King Cheops' ancestors!

The absence of the twenty-eighth slot in the western

banquette, whose place is now taken up by the opening of the 'well', serves

to confirm the views expressed by Petrie; to wit, that the connection of the

Grand gallery wit hthe primitive shaft used by descending stonecutters, a

hole drilled through the masonry, was a task undertaken after the pyramid

had been built.

That the Grand gallery is simply the gallery of the ancestors

is corroborated by two ancient Arab authors. Muhammed Ishaq ibn al-Nadim,

quoted by Ahmed ibn Ali al-Maqrizi, writes: "�A passage pierces this

pavement�; the arch is made of stone and one sees there portraits and

statues standing or resting and a quantity of other things, the meaning of

which we do not understand." And Ibrahim Wassif Shah writes: "�In the

Eastern pyramid, chambers had been built in which the stars and heavens were

depicted, and in which was amassed what Surid's forebears had accomplished

in the way of statues." (Undoubtedly, the manuscript's text has been

misreported; it should read: "�in which were amassed the statues that were

done of Surid's forebears.")'.

Comment

- If Pochan is correct then this is of course,

important. The question is, how many Kings were

there before Choeps? Also, perhaps it is worth counting the slots in the

valley temple (note that they are far less deep.) Note also that we can see

the same kind of damage at Hatshepsut's temple. (see

below)

Context

- The following two pictures show the same style of building corbelled

constructions from inside other Egyptian pyramids:-

Corbelled Roofs from inside the Red pyramid, and the

'unfinished' Meidum pyramid.

Here is an internal feature similar to that of the 'great' pyramid. There

is a strong suggestion, especially in the 'Red' pyramid, of a contemporary

design (Note - Similar designed stone on entry to chamber, Lack of internal

funerary scripts etc). The same feature can be seen in the 'Bent' pyramid.

Mendelssohn says the following:-

Extract from Mendelssohn - An

inscription found near the Red pyramid mentions the 'two pyramids of Snofru'

and it was at first assumed that the other Snofru pyramid must be that at

Meidum. More recent work at the bent pyramid has, however, shown that this

one, too, definitely belonged to Snofru. We are left with what Sir Alan

Gardener called the 'unpalatable conclusion that Snofru did possess three

pyramids'.

|

|

2.28)

The 'Antechamber' and 'Portcullis' System.

The theory that the antechamber once housed a 'portcullis' system is

generally accepted, although a model of the system that explain all

the features of the antechamber is still forthcoming. The best research in

this area came originally from Lepre, who studied the question in depth.

While his findings are far from conclusive, they are reasonable and remain

the only conclusion of any merit. First, an extract from Petrie:

'The

rubbish that had accumulated from out of Mamun's Hole was carried out of the

Pyramid by a chain of five or six men in the passage. In all the work I left

the men to use their familiar tools, baskets and hoes, as much as they

liked, merely providing a couple of shovels, of picks, and of crow-bars for

any who liked to use them. I much doubt whether more work could be done for

the same expense and time, by trying to force them into using Western tools

without a good training. Crowbars were general favourites, the chisel ends

wedging up and loosening the compact rubbish very easily; but a shovel and

pickaxe need a much wider hole to work them in than a basket and hoe

require; hence the picks were fitted with short handles, and the shovels

were only used for loose sand. In the passage we soon came down on

the big granite stone which stopped Prof. Smyth

when he was trying to clear the passage,

and also sundry blocks of limestone

appeared. The limestone was easily smashed then and there, and carried out

piecemeal; and as it had no worked surfaces it was of no consequence. But

the granite was not only tough, but interesting, and I would not let the

skilful hammer-man cleave it up slice by slice as he longed to do; it was

therefore blocked up in its place, with a stout board across the passage, to

prevent it being started into a downward rush. It was a slab 20.6 thick,

worked on both faces, and one end, but rough broken around the other three

sides; and as it lay flat on the floor, it left us 27 inches of height to

pass down the passage over it. Where it came from is a complete puzzle; no

granite is known in the Pyramid, except the King's Chamber, the Antechamber,

and the plug blocks in the ascending passage. Of these sites the Antechamber

seems to be the only place whence it could have come; and

Maillet mentions having seen a large block (6 feet by 4) lying in the

Antechamber, which is not to be found there now. This slab is 32 inches wide

to the broken sides, 45 long to a broken end, and 20.6 thick; and,

strangely, on one side edge is part of a drill hole, which ran through the

20.6 thickness, and the side of which is 27.3 from the worked end.

This might be said to be a modern hole, made for smashing it up, wherever it

was in situ; but it is such a hole as none but an ancient Egyptian would

have made, drilled out with a jewelled tubular drill in the regular style of

the 4th dynasty; and to attribute it to any mere smashers and looters of any

period is inadmissible. What if it came out.

of the grooves in the Antechamber, and was placed

like the granite leaf across that chamber? The grooves are an inch wider, it

is true; but then the groove of the leaf is an inch wider than the leaf. If

it was then in this least unlikely place, what could be the use of a 4-inch

hole right through the slab? It shows that something has been destroyed, of

which we have, at present, no idea'. 'The

rubbish that had accumulated from out of Mamun's Hole was carried out of the

Pyramid by a chain of five or six men in the passage. In all the work I left

the men to use their familiar tools, baskets and hoes, as much as they

liked, merely providing a couple of shovels, of picks, and of crow-bars for

any who liked to use them. I much doubt whether more work could be done for

the same expense and time, by trying to force them into using Western tools

without a good training. Crowbars were general favourites, the chisel ends

wedging up and loosening the compact rubbish very easily; but a shovel and

pickaxe need a much wider hole to work them in than a basket and hoe

require; hence the picks were fitted with short handles, and the shovels

were only used for loose sand. In the passage we soon came down on

the big granite stone which stopped Prof. Smyth

when he was trying to clear the passage,

and also sundry blocks of limestone

appeared. The limestone was easily smashed then and there, and carried out

piecemeal; and as it had no worked surfaces it was of no consequence. But

the granite was not only tough, but interesting, and I would not let the

skilful hammer-man cleave it up slice by slice as he longed to do; it was

therefore blocked up in its place, with a stout board across the passage, to

prevent it being started into a downward rush. It was a slab 20.6 thick,

worked on both faces, and one end, but rough broken around the other three

sides; and as it lay flat on the floor, it left us 27 inches of height to

pass down the passage over it. Where it came from is a complete puzzle; no

granite is known in the Pyramid, except the King's Chamber, the Antechamber,

and the plug blocks in the ascending passage. Of these sites the Antechamber

seems to be the only place whence it could have come; and

Maillet mentions having seen a large block (6 feet by 4) lying in the

Antechamber, which is not to be found there now. This slab is 32 inches wide

to the broken sides, 45 long to a broken end, and 20.6 thick; and,

strangely, on one side edge is part of a drill hole, which ran through the

20.6 thickness, and the side of which is 27.3 from the worked end.

This might be said to be a modern hole, made for smashing it up, wherever it

was in situ; but it is such a hole as none but an ancient Egyptian would

have made, drilled out with a jewelled tubular drill in the regular style of

the 4th dynasty; and to attribute it to any mere smashers and looters of any

period is inadmissible. What if it came out.

of the grooves in the Antechamber, and was placed

like the granite leaf across that chamber? The grooves are an inch wider, it

is true; but then the groove of the leaf is an inch wider than the leaf. If

it was then in this least unlikely place, what could be the use of a 4-inch

hole right through the slab? It shows that something has been destroyed, of

which we have, at present, no idea'.

These 'anomalous' granite stones were concluded by Lepre to

be parts of the original portcullis system.

Extract from 'Giza the Truth' - 'It is often suggested

that no fragment of the three missing portcullis' has ever been found, and

from this many alternative researchers�and even some Egyptologists�deduce

that they were never even fitted. In the first instance, the continued

presence of the counterweights�which are above the level of the passage and

therefore would not obstruct the progress of an intruder�suggests to us that

the portcullis' were originally in place but were broken up by the early

robbers. Again we would suggest that, as with the "Bridge Slab", the debris

from this operation would have been cleaned up by restorers. However, in

addition to this evidence, Lepre produces a real coup de grace on the

matter:

he has matched the four blocks of fractured granite

found in and around the edifice

to the dimensions of the portcullis'.

Extract from Petrie - In brief, each

of the main slabs would have been a minimum of 4 feet high by 4 feet

wide�probably more depending on the degree of overlap into the slots�and

most significantly about 21 inches thick (to allow a tolerance of � inch in

the slots). He examined the four blocks�one lies near the pit in the

Subterranean Chamber, another in the niche in the west wall just before the

entrance to this chamber, another in the Grotto in the Well Shaft, and

another outside the original entrance�and established that whilst they were

all less than 4 feet in height and width, they were all 21 inches thick!

(Note that there is a loose block of granite in the King's Chamber, but this

is known to come from the floor thereof and was therefore omitted from the

analysis.) As if this were not sufficient evidence, he found that three of

the four blocks have 3� inch holes drilled in them�in fact the one in the

pit has two, and the one near the entrance three. Furthermore, the holes in

the latter are spaced 6� inches apart. So he established that not only do

the holes have the same diameter as the channels for the ropes in the south

wall of the Antechamber, but they are also spaced the same distance apart.

Although Lepre is unable to provide a foolproof explanation as to how these

four fragments ended up in their present locations�he suggests a variety of

high jinks by early visitors to the monument�nevertheless this strikes us as

pretty convincing evidence that these are indeed fragments of the original

portcullis'.

This is of course, a hugely important finding. Should the

other stones indeed be a part of an original 'portcullis' system, what did

it look like and why was it there? Why is there a piece in the 'Grotto'? Can

we track the movement of these pieces with the historical accounts? There do

not seem to be enough pieces, but the size of them suggests that they may be

remnants.

Extract from the Edgar Brothers: Vol I; (In reference to the

granite block in the descending passage) - 'We also instructed our men to

shift the position of the large limestone block which then lay diagonally

across the passage floor a little distance above the granite block'.

(14) We can assume for now that it is the same stone that now sits in the

'pit'. (see photo below). In Vol I

(14), Plates LVIII and LIX show the block in the recess before the subterranean chamber.

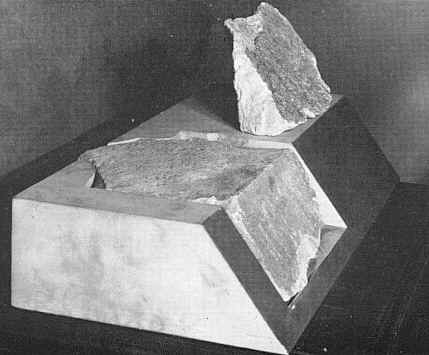

Four granite slabs from inside the Great pyramid - Are these

remnants

of the portcullis system?

From left to right - Bottom right of the descending passage (found by Petrie

half way down the descending passage), outside the main entrance and

one on a ledge in the subterranean pit.

A

fourth granite block lies in the Grotto.

Question

- How are these stones to be explained in the context of the 'tomb' theory?

The remaining slabs were never intended to fall and it appears possible to

bypass the system regardless. Is this system evidence that the structure may

have had a function before it was sealed?

Extract from Edgar Brothers: Vol I - (In reference to the

Portcullis system) 'Some writers have suggested that the three opposite

pairs of broad vertical grooves originally contained sliding portcullises of

granite, which at one time cut off all entrance to the Kings Chamber�this

suggestion was supported by Col. Howard Vyse�His idea was that, during the

lifetime of the King, the now missing portcullises were suspended above the

floor of the Ante-chamber on a level with the top of the low passages, just

as the Granite leaf is now suspended; but that after the death and

internment of the King, they were one by one lowered gradually by chiseling

away the supporting granite immediately below them on the side walls, until,

sinking down by their own weight, they finally rested on the floor'.

(14)

The Edgar's noticed however, that: '...when, however, we begin

to investigate the subject more closely� we find that there are distinctive

peculiarities about the "granite leaf", which make it certain that it, at

all events, had not been intended by the architect to serve as a

portcullis'. (14) So what was the remaining stone for. It is of interest that the 'Boss' is

well recorded in Egypt. It was believed to have been left on the stones in

order to manoeuvre them more easily, although in this particular case it is

worth noting the following observation: 'The granite leaf appears to be

an inch narrower than its corresponding grooves in the wainscots�Close

examination shows that this difference is made up by narrow one-inch

projections or rebates on the north face of the leaf, which make it fit

tightly into its grooves. With the exception of these rebates (which are

evidence of special design), the whole of the north face of the leaf has

been dressed or planed down one inch, in order that one little part in the

middle might appear in relief'.

(14)

The 'Boss' as seen

from underneath. The fact that it was left in-situ suggests that it had as

symbolic function.

Pochan emphasizes that the whole system must have been closed off at some

time. He says:

'Contrary to the claims made by certain authors�the three

portcullises were actually set in place and lowered. The south wall, in

fact, shows clear, significant traces of damage, which would be totally

inexplicable had the passage to the king's chamber been open. It is obvious

that the damage done to the Antechamber's south wall was effected from the space located above the lowered portcullises. The

first despoilers, having experienced great difficulty in trying to raise the

granite block closing off the entrance to the antechamber, were unable to

force the portcullises and had to settle for making a man-sized hole in the

upper part of the corridors wall, opening onto the chamber of the

sarcophagus'. However, this raises the question: Why was the antechamber

then subsequently cleared of blocks?

In a final note, it is worth quoting Petrie over the granite

portcullis stones of the Khafre's pyramid when he says:

'The skill

required to turn over and lift such a block, in such a confined space, is

far more striking than the moving of much larger masses in the open air,

where any number of men could work on them. By measuring the bulk, it

appears that this portcullis was nearly two tons in weight, and would

require 40 to 60 men to lift it; the space, however, would not allow of

more than a tenth of that number working at it; and this proves that some

very efficient method was used for wielding such masses'.

(14)

|

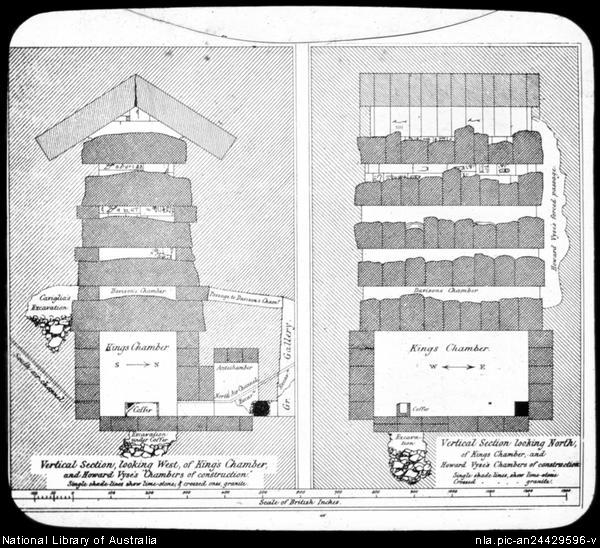

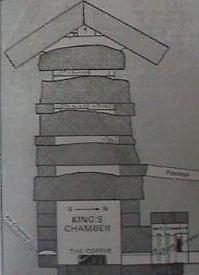

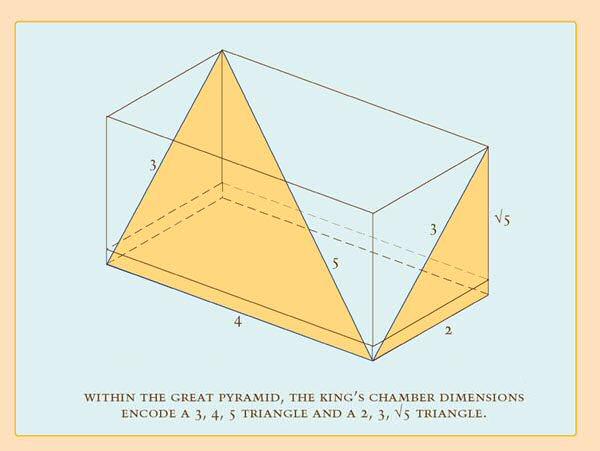

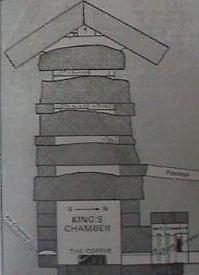

2.29)

The Kings chamber.

Only called the 'King's Chamber' because Arabs buried their kings in flat-roofed chambers and

Queens in corbelled chambers.

2.291) 'Explosion' or 'Subsidence'.

It has been noted that the Kings chamber has the appearance

of having been

expanded or shifted, suggested to have been caused by an

explosion. An interesting idea considering both al-Mamun and Vyse used

explosives (although we must assume it was done before - as it was plastered

over). So if not an explosion, what caused the huge stones to break?

Need to take into account the fact that the 'star-passages' were

still blocked but correctly aligned still and considered 'candle holder

areas' by Petrie until they were opened by him. The fact that the supporting

beams of the chamber were plastered up 'by hand' definitely points towards

movement within the chamber after its finish. If something had exploded so

violently within the chamber, how did the walls, ceiling and 'coffer' remain

in such good condition?

If movement has occurred however, it needs to be considered

what the cause was, which other part of the pyramid appears affected (except

possibly the lack of casing stones). Le-Mesurier mentions two candidates,

one in 908 AD and the other in 1301AD. (Apparently 30,000 people perished in

Egypt during the 908 earthquake).

Davison

(2), came to the

conclusion that there had been movement within the pyramid.

How these repairs are to be explained is another mystery.

There is no way that the damage was caused by the repairers. Anyone who

would go to the lengths of plastering the walls of the king's chamber in

order to hide the cracks, would also, one would presume, fix all the damage

on the way out. This was not done.

It has been pointed out that 'Davidson's' chamber, was

clearly 'cut through after the blocks had been put in place'.

(10)

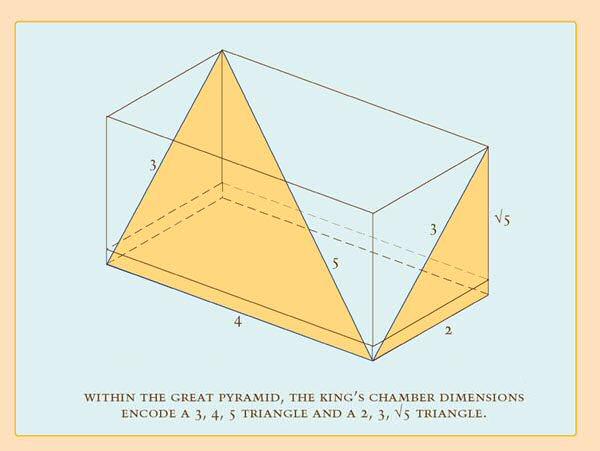

2.292)

The 'Sarcophagus' or 'Coffer'.

Pochan

(16)

said of it:

'The sarcophagus, made of Aswan

granite, was equipped with a sliding dovetailed lid; it is similar to many

other sarcophagi, particularly that of Unas and most especially those of the

great mastaba of Meidum and the pyramid of Kephren. Upon closing, three rods

inserted into holes in the lid dropped into three corresponding holes in the

cask, which were not as deep as the length of the rods'.

The Kings Coffer (with removed floor stone in

background)

(The Volume of the

interior is equal to half the Volume of the exterior...)

T he coffer's dimensions also demonstrate the application of a 3:4:5

triangle - incidentally demonstrating the geometric method of creating the

angle of slope for Khafre's pyramid.

Note - It

is often claimed (erroneously), that the Coffer would have had to have been

placed in the King's chamber from above as it is too big too fit through the

passage entry.

'Petrie's measurements of

the passage were 41.08 to 41.62 inches wide by 47.13 to 47.44 inches high,

and his dimensions of the box were...41.97 inches outside width, and 38.12

inches outside height'.

(1)

(Answer... think about

it.. think about it... Turn the box

sideways)

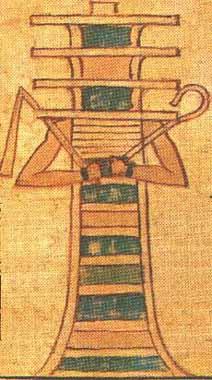

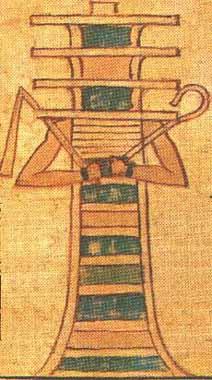

2.293)

The 'kings

chamber' as a representation of a 'Djedt', (Osiris's backbone/spine).

The

Djed is also known as the Djed column, Djed pillar, Tet, Tet Column, or Tet

pillar. It is associated with Osiris and is a metaphor for the phallus.

The Djed pillar hieroglyph means 'stability'.

The source of the imagery is however, shrouded in time. It is clearly

pre-dynastic in origin.

The Djed Pillar is the oldest symbol of Osiris and was of

great religious significance to the ancient Egyptians. It is the symbol of

his backbone and his body in general. The Djed is represented on two ivory

pieces found at Helwan dating to the first dynasty, evidence that the use of

this symbol is at least that old. The djed pillar also came to be equated

with the king's backbone, often painted in the bottom of the coffin, under

where the spine would lay.

|

|

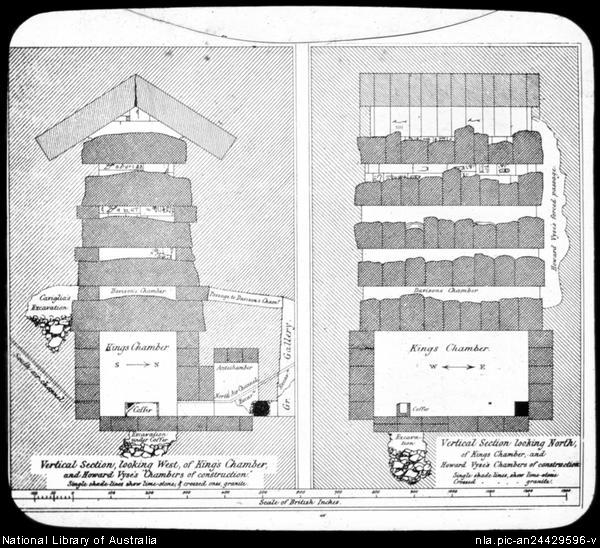

2.30)

The Relieving Chambers.

The excavations by Col. Vyse in the 1800's opened the 'relieving

chambers'. Above the roof of the 'Kings chamber is a series of five

relieving chambers formed by granite slabs, which it is argued, were

essential to support the weight of the stones above and to distribute the

weight away from the burial chamber. The top chamber has a gabled roof made

of limestone blocks. In these chambers, are found the only inscriptions in

the whole pyramid. The lowest of the 5 Ceiling Chambers was found to contain

a black dust, possibly the remains of insects entombed in construction

(Exfoliate). The limestone gable of the highest chamber was the only place

(other than the Mid Chamber and some parts of the Grand Gallery) that

contains salt deposits.

In response to the idea that these chambers were for

relieving weight, one has to ask why they were not a feature of the lower

'Queens' chamber, and more to the point, it has been shown that they have no

'relieving' capacity whatsoever.

Petrie said of them:

"All these chambers over the King's Chamber are floored

with horizontal beams of granite, rough dressed on the under

sides which form the ceilings, but wholly unwrought above.

These successive floors are blocked apart along the N. and

S. sides, by blocks of granite in the lower, and of

limestone in the upper chambers, the blocks being two or

three feet high, and forming the N. and S. sides of the

chambers. On the E. and W. are two immense limestone walls

wholly outside of; and independent of; all the granite

floors and supporting blocks. Between these great walls all

the chambers stand, unbonded, and capable of yielding freely

to settlement. This is exactly the construction of the

Pyramid of Pepi at Sakkara, where the end walls E. and W. of

the sepulchral chamber are wholly clear of the sides, and

also clear of the sloping roof-beams, which are laid three

layers thick; thus these end walls extend with smooth

surfaces far beyond the chamber, and even beyond all the

walls and roofing of it, into the general masonry of the

Pyramid."

Pyramids and Temples of

Gizeh, 1883

The photo (right) is of depressions or 'bowls' found in the

stones of the top

chamber, called the 'Davidson's' chamber. They are reminiscent of the

Stonehenge lintel-stones but their actual purpose is unknown. All the

granite stones were flattened on their undersides but were left semi-worked

on their upper surfaces.

It appears that it was considered important enough to

smooth the bottom faces, even though they were placed in a position

that would never be seen again.

These are the

amongst the heaviest stones in the pyramid and were quarried and shipped

from Aswan from over 500 miles south. There seems to be no logic behind such

an investiture of energy, and the feature is completely unique in Egyptian

architecture.

From an engineering perspective, Rudolf Gantenbrink

suggested that without these upper chambers the roof beams of the King's

chamber, which deflect about 50% of the load into the horizontal, would have

pushed against the south end of the Grand Gallery. To avoid this, he says

that the builders had to lift the roof above the relevant static structure

of the Grand Gallery. As this seems to be the only reasonable explanation at

present, one must assume that in terms of engineering, they were designed

not to prevent downwards pressure on the 'King's chamber, but rather to

prevent sideways pressure onto the 'Grand Gallery' which sits only metres to

the north of them.

The unfinished tops of the stones in Lady Arbuthnots's

Chamber (left).

The 'Quarry-marks' or

'Graffitti':

The first level of the relieving chambers

were entered, probably by a repair crew early in the life of the Great

pyramid.

The higher chambers were later shown to have several 'graffitti' marks on

them, presumably from the original builders, as some of the marks can be

seen to continue into currently inaccessible places. These marks represent

the only actual evidence that the pyramid was commissioned by Khufu (or

Khnum-Khufu).

(Original 1837

Drawings of the Graffitti)

It

has been suggested that the quarry marks are not original, but were added by

Vyse in order to gain fame. In response to this, it is noted that some can

be seen to run behind existing masonry. As they are the only direct evidence

of who was responsible for building the pyramid, it is important to know if

they are fake or genuine.

(More about the

Quarry-marks)

|

|

2.31)

The

'Star' shafts.

The so-called 'star-shaft's' were predicted (for air conditioning) before they were

found. It was Col Vyse who first cleared out the air shafts

to the King�s Chamber and it is said that once opened, an immediate rush of cool air entered

the King's Chamber which maintains an even temperature of 68�

to this day regardless of the weather outside. Although this fact is apparent, it is

questionable whether this was their original function.

The extraordinary amount of work that builders undertook in order to

complete the 'star-shafts' makes it clear that they were considered a

fundamental part of the design. They do not appear in any other Egyptian

structure, and therefore have no context in which to place them. There are

two sets of shafts in the great pyramid: One set leading from the 'Queens

chamber' and another from the 'kings chamber'. The set from the Queens

chamber was left sealed at both the top and bottom, while those in the kings

chamber were left open. Gantenbrink's robotic exploration of the shafts

leading from the Queens chamber has aroused much debate in

recent years.

Gantenbrink

also observe that different styles of masonry were used in the construction

of the tunnels.

Diagram Illustrating the different styles of masonry

used in the construction of the 'Star' passages.

'Queens' Southern star shaft.

'Kings' Northern star shaft (Rubbish photo!)

Gantenbrink writes that the inclinations of the upper shafts could be measured by

drawing a line between the beginning and end of the shaft, and that the

shafts, although bending horizontally, were extremely precise. With a laser

measuring device he didn't find any differences in the width of the shafts

of greater than 0.005 m. Even more fantastic is the fact that the

beginning and the end of a shaft are precisely on one line, even though the

shafts bend in between!.

An observation of the location of the

King's chamber shafts shows that the place at which they entered the chamber

was very specific. They enter at an identical place as the shafts in

the queens chamber, opposite each other and just above the first level of

masonry on the north and south walls. This position was clearly important as

both sets of shafts had to be made so as to manoeuvre around the 'Grand

Gallery', something which would have caused the designers and builders a

great deal of extra consideration.

The

northern 'Queen's' shaft shows settling which might have occurred due to an earthquake

during the building phase; Gantenbrink concluded that the current shaft

inclination might vary from the planned angle by up to 2�. The southern

shaft, on the other hand, has the same accuracy seen in the upper shafts.

'Queens' Southern star shaft.

'Kings' Northern star shaft (Rubbish photo!)

Gantenbrink says - 'I was convinced that the shafts mark

the first construction phase of the pyramid. They constitute basic elements

of great importance. Put simply, a stone structure of such magnitude, built

up in layers over a period of many years, is a sufficiently gargantuan

undertaking to daunt any builder.

But adding diagonal shafts through such a structure so

complicates the task that it becomes a builder's nightmare. The

builders must have ascribed great significance to the shafts; otherwise they

would never have let themselves in for such a massive constructional

headache'.

The existence of the shaft's raises

several interesting questions such as:

Why build two sets of shafts?, Why have a horizontal section at the bottom

of each.?

Why were the top two open while the bottom two were built closed off at both

ends? How are we to explain the design of the top ends of the Queen's

shaft (The 'doors' with handles and an empty space behind)?

T he

current theories for these shafts are:-

1) They are 'Ventilation' shafts: Apart form the fact that the lower shafts were

closed at both ends, it also seems contradictory

that they would leave

open shafts into a Pharaohs chamber, as this would have potentially

exposed the chamber to birds, snakes, rats,

insects, water etc. Something unheard of in terms of Egyptian funerary

chambers. Only one shaft would have been necessary for ventilation. One also

has to ask for whom they were intended to ventilate

2) They are 'star' shafts: This particular theory has gained

weight in recent years although there are some stubborn arguments against

it: Apart from the obvious fact that the queen's chamber shafts were built

closed off at both ends, all the shafts bend, often with extreme angle

fluctuations so that none of them ever pointed directly at anything. While

it is true that certain relevant stars did/do pass in front their entrances

(at different chronological times), their placement on a north - south axis

makes it a simple fact of nature as the sky revolves from east to west.

There is still no conclusive theory to explain all four shafts in this

context. Graham Hancock's theory has been shown to untenable as the stars he

proposes were never in the sky together in the required positions.

3) They were used for religious/symbolic purposes: Although

there are no

other pyramids which show similar features this theory seems possible,

although why this pyramid alone was singled out

for this is uncertain. The suggestion that they were placed there for the passing of the

soul is highly questionable in terms of the queens chamber? Nothing contemporary is recorded

concerning this practice.

Exploration of the

Queens Shafts.

The Queens Chamber shafts were originally sealed with 5"

(12.5cm) of uncut masonry on their inside ends, the blocks they start from

having been hollowed out for several feet behind. The following is Piazzi

Smyth's record of the Dixon brothers' own testimony:

'Dr. Grant and Mr.

Dixon have successfully proved that there was no jointing, and that the thin

plate was a 'left', and a very skilfully and symmetrically left, part of the

grand block composing that portion of the wall on either side'.

(10)

The Queens northern star-shaft has been explored at least

twice. Once in 1872 by Waynman Dixon and D. R. Grant,

and then again in 1993 by Gantenbrink. The following is a list of

objects found in the shaft:-

Objects observed in the 1872 expedition:

1.

A green stone (granite) ball (weighing 1lb 3oz).

2.

A slat or rod of Cedar wood about 13cm long. (Now missing but

recorded by Piazzi Smyth)

3.

A bronze or copper hook, 5 cm's long,

with a part of a wooden handle still attached.

Waynman Dixon noted in his

diary:

"This thing is bronze green and with strong encrustations

agglutinated. Once riveted on to a wooden handle."

Objects observed in the 1993 expedition:

1 .

A piece of wood with holes (that match the rivets on the bronze item).

2.

A

2m + length of wood resembling a staff with a portion missing.

3.

Various pieces of unidentified material, located in two areas

of the shaft.

4.

A large rectangular object can be seen at the upper end of the shaft

attached to the 2-meter length of wood.

The Gantenbrink experiment also found a metal pole in the

Queens shaft. It has been reasonably suggested that the parts from both

exploration are parts of the same object/s, which were broken. The metal

pole is believed to be a remnant from the 1872 search. Could it be that the

'hook and handle' are remains of an even earlier attempt to explore the

shaft.

The Gantenbrink experiment was carried out on the 'Queens'

chamber star-shaft. A remote-controlled miniature vehicle was sent up to

photograph the upper section of the shaft. It reached a dead-end. The shaft

was blocked but features of the end-stone suggested that there might be

something beyond it. After the 1993 experiment, no further research was

allowed on the shafts by Gantenbrink.

The 'Queens'

northern shaft.

The 'Queens'

southern shaft.

The

'Doors'.

Queens Northern Shaft.

Queens Southern Shaft.

On 18 September 2002, the 'Pyramid Rover' was sent up the

northern shaft, this time off-the-air. Navigation was difficult due to four

sharp bends. Another "stone partition, or door" at the end of the shaft,

again with two copper fittings, was discovered. The Queens southern shaft's

'doors were found to be the

same distance (211 feet) from the Queen's Chamber.

The broken copper 'Handle' with fallen piece on the floor.

Note: the first picture of this shows it as complete.

The 'doors' with the copper 'handles' found at the end of the

queens 'star-shafts', support the idea that the shafts are neither for

ventilation or for astronomical purposes.

In 2002, another robot, the Pyramid Rover designed by iRobot

of Boston, was sent to the end of the southern shaft to investigate further.

The robot drilled a 3/4-inch hole in the slab and, on 17 September, a

miniature fibre-optic camera was inserted to reveal a rough-hewn blocking

stone lying 7 inches beyond the original southern shaft slab.

.jpg)

Chris Dunn reports that there is evidence of a vertical shaft

going down in the small chamber behind Gantenbrink's slab. The photo above

seems to support this. Notice the area on the bottom left.

This

report was posted on the Graham Hancock Website.

News

flash from Giza as of December 1, 1999

What

lies beyond the "door" at the upper end of the narrow passage leading up

from the "Queen's Chamber" in the Great Pyramid may have recently been

explored, in secrecy. It

has been reported to us that on October 20, 1996, the Gantenbrink experiment

has now been realized. As previously reported in the Egyptian Gazette

newspaper, Zahi Hawass' choice of Dr. Farouk El Baz to complete this project

to explore the passage, apparently has come to fruition.

This

story was obtained from two separate security guards at Ghiza, and

independently confirmed via a media person working with the Sphinx

expedition of Dr. Joseph Schor, currently in the excavation phase. This is

the report:

At

the end of the ascending passage, 8 inches square, leading from inside the

Great Pyramid's "Queen's Chamber" is a small "door" with two

metal "handles." On October 20, 1996, Dr. El Bas and two assistants

sent a fibre optic camera lens through a flaw in this door. What was

allegedly found was a 2 meter by 1.5 meter chamber inside of which was a

statue. The statue seemed to be in the image of a black male, holding an

Ankh in one hand. On the opposing wall of this chamber was a round shaped

passage leading out.

It has been suggested that because the 'Queens' shafts

terminate before the exterior, (the northern one apparently at masonry level

50, the 'Kings' chamber), that there was a 'change of plan' in the

construction. If however this was the case, why build them sealed off at the

bottom ends and why

did work on the southern shaft continue above the 'Kings' chamber level.

Comment

- While the exact function of the shafts is a mystery, the expenditure of

effort presumes them to be most important features. The shafts are a

point that requires more interpretation. Again the world awaits the Egyptian

authorities response. It seems bizarre therefore that no effort is being

made to pursue this point.??

|

(Return to Top)

|

External Features of the Great pyramid: |

|

2.11).

The Missing Capstone (Benben):

The missing capstone was only

first mentioned by