|

by Captain Charles W. Wilson, R. E., 1886

PREFACE

The Survey of Jerusalem was undertaken

with the sanction of the Right Hon. Earl de Grey and Ripon, Secretary of

State for War, in compliance with the request of the Very Rev. Dean Stanley;

who, on the part of a Committee interested in endeavouring to improve the

sanitary state of the city, requested his Lordship to allow a survey of it

to be made under my direction, with all the accuracy and detail of the

Ordnance Survey of this country, the Committee undertaking at the same time

to pay the entire cost of the proposed survey, which was estimated at about

500 pounds.

I consequently drew up minute

instructions for making the survey; and selected Capt. Charles W. Wilson,

R.E., and the following party of Royal Engineers from the Ordnance Survey,

to execute the work, viz., Serj. James McDonald, Lance-Corp. Francis Ferris,

Lance-Corp. John McKeith, Sapper John Davison, Sapper Thomas Wishart; and

they left England on the 12th September 1864, arrived in Jerusalem on the

3rd October, and immediately proceeded to the work of selecting and

measuring base lines, and establishing the triangulation for the survey of

the city and the neighbourhood, which is represented on Plate I.

In addition to the requirements of the

Committee, I sent out a Photographic Apparatus to enable Serj. McDonald, who

is both a very good surveyor and a very good photographer, to take

photographs of the most interesting places in and about Jerusalem; and I

instructed Capt. Wilson to examine the geological structure of the country,

and to bring home specimens of all the rocks, with their fossils.

I also made application through the

Foreign Office for a letter to be sent to the Turkish Government, requesting

that instructions might be sent to the Governor of Jerusalem to afford Capt.

Wilson and the party every assistance and protection in the execution of

their work; and our thanks are due to his Excellency Izzet Pasha, for the

cordial manner in which, under his orders, they were enabled to enter the

Mosque of Omar, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Citadel, and other

public buildings, and to make minute surveys of them.

To Noel T. Moore, Esq., Her Majesty's

Consul, to the Consuls of other nations, and to the principal residents, our

thanks are also due, as well as to Sir Moses Montefiore, who was so obliging

as to send out letters of introduction for Capt. Wilson to the Hatram Banhi

and principal resident Jews in the city.

Our thanks are also due to the

Directors of the Peninsular and Oriental Company for their liberality in

allowing the party to go in their steamers to and from Alexandria at a

reduced rate, and thus contributing towards the cost of the Survey.

LEVELLING FROM THE MEDITERRANEAN TO

THE DEAD SEA

Soon after the party bad arrived

at Jerusalem my late lamented friend Dr. Faleoner brought under the

consideration of the Royal Society, and of the Royal Geographical Society;

the great importance of availing themselves of the opportunity of our having

a party of Ordnance Surveyors in Palestine to get the difference of level

between the Mediterranean and the Dead Sea accurately determined, and these

Societies were pleased each to place 100 pounds. towards the cost of this

work at my disposal. I consequently sent out instructions for this work

being done, and subsequently for the levelling from Jerusalem to the Pools

of Solomon, which, in consequence of the great discrepancy between the

levels given by different civil engineers, the Syrian Improvement Committee

were anxious to have determined, and observations made on the ancient and

present water supply to the city. The sum of 50 pounds. was placed, through

their Honorary Secretary, the 'Rev. Herman Schmettat', at my disposal for

this purpose.

The party completed its labours, and

embarked at Jaffa on the 16th June, and returned to England on the 10th July

1865, without any casualty and without having suffered much from sickness...

The Lords Commissioners of Her

Majesty's Treasury have on my recommendation sanctioned the engraving and

publication of the results of the survey, and they are now given to the

public.

Since the completion of this survey a

Society has been formed under the patronage of Her Majesty the Queen, which

is called the "Palestine Exploration Fund," the first meeting of which was

held on the 22nd June 1865, his Grace the Archbishop of York in the chair,

and I am much gratified to state that, from the very satisfactory manner in

which Capt. Wilson carried out my instructions for the survey of Jerusalem,

the levelling to the Dead Sea, etc., he has been selected to go out as the

chief director of the explorations to be made by the new society which has

been formed; but. although I am deeply interested in the success of this new

expedition, in my official capacity have nothing whatever to do with it...

TOPOGRAPHY:JERUSALEM

With this preliminary sketch of

the geological structure of the country, we are prepared to under-stand the

peculiar character of the topography of the country in and about Jerusalem.

The effect of denudation has been to

remove all the nummulitic limestone, with the exception of that which

occupies the summit of the high ground extending from Mount Scopus to the

Mount of Olives and the Mount of Offence, and that which occupies the summit

of the Mount of Evil Council.

The city itself is built on the

formation called " Missie," but denudation has exposed the " Malaki and the

"Santa Croce" formations, as previously described.

The Santa Croce formation is largely

exposed to the west of the city, in the neighbourhood of the Convent of the

Cross; and it is from the quarries in this quarter that the marble easing of

the Holy Sepulchre, the shafts of the beautiful Corinthian columns in the

Mosque-el-Aksa, and the greater part of the ornamental stones used in the

ancient and modern buildings were obtained.

The ground occupied by the city is

bounded on the west and south by the valley of Hinnom, and on the east by

the valley of Jehoshaphat or of the Kedron; these unite at the fountain of

Joab, about half a mile to the south of the city, and from thence the valley

with its water-course, under the name of the Kedron, descends to the Dead

Sea. The promontory, thus surrounded by deep valleys on the west, south, and

east, is divided by a smaller valley, intersecting the city from north to

south, turning from the Damascus gate by the pool of Siloam to the valley of

the Kedron, and called the Tyropean valley, or valley of the a branch from

which ran westward to the citadel. Another small valley to the north of the

Harem-es-Sherif entered the valley of the Kedron from the NW at St.

Stephen's gate.

The ground is thus formed into two

spurs, which run out from the higher ground on the north-west of the city,

the western and highest of which is the Mount Zion of the Bible, and the

"Upper "city" of Josephus; whilst the eastern is Mount Moriah, upon which

the Temple formerly stood, and the Mosque of Omar, or Dome of the Rock, at

present stands.

MOUNT ZION

The citadel occupies the narrow neck of

ground between the valley of Hinnom and the Tyropean valley, and barred the

only level approach to the ancient city (for that part of the city which

lies to the north of the citadel is, comparatively speaking, a modern

addition), and which, being surrounded by valleys on every other side, and

being 110 feet higher than Mount Moriah, must have been a very strong

commanding position for a small city.

"David and all Israel went to

Jerusalem, which is Jebus. David took the castle of Zion, which is "the city

of David, And David dwelt in the. castle; therefore they called it the city

of David." ---l Chron.,

xi.

"David took the stronghold of Zion, the

same is the city of David. So David dwelt in the fort, and "called it the

city of David "---2 Samuel,

v.

"David began the siege of Jerusalem,

and he took the lower city (Acra) by force, but the citadel "held out

still." When David had cast the Jebusites out of the citadel, he also

rebuilt Jerusalem, end "named it the city of David, and abode there all the

time of his reign."---Josephus " Antiquities of the

Jews, Book vii. ch. iii.

"Beautiful for situation, the joy of

the whole earth, is Mount Zion, on the sides of the north, the 'city of the

great king.' "---Psalms, xlviii.

There can, therefore, be no doubt but

that this hill is Mount Zion, for it has been so called in all subsequent

histories, and is so called at present.

MOUNT MORIAH

From the 21st chapter of the 1st

Chronicles we learn that David bought the threshing floor of Ornan the

Jebusite, and "built there an altar unto the Lord."

Then David said, (First Chronicles,

xxii), "This is the house of the Lord God, and this is the altar of "the

burnt offering for Israel."

"Then Solomon began to build the house

of the Lord at Jerusalem in Mount Moriah, in the place that David had

prepared in the threshing floor of Oman the Jebusite."---2 Chronicles iii.

No one has ever questioned that the

Temple formerly stood within the Haram-es-Sherif; and therefore there can be

no doubt but that the hill on which the Haram stands has been properly named

Mount Moriah.

Now, although on the sketches of the

ground the contours and the levels indicate the hills and valleys which have

been described, these features are defined with less of that sharpness and

distinctness which they must have had in former times. We learn from history

and from actual exploration underground that the Tyropean valley has been

nearly filled up, and that there is a vast accumulation of ruins in most

parts of the city.

Thus, for example, it has been found,

by descending a well to the south of the central entrance of the Haram, that

there is an accumulation of ruins and rubbish to the extension of 84 feet;

and that originally there was a spring there, with steps down to it, cut in

the solid rock.

Now, if we examine the photograph of

the rocks and houses to the west of the valley, we see that the side of the

valley was there nearly precipitous (see Photograph No. 31.a.), and that the

ground southward was also very steep, if not also precipitous.

So again, if we refer to the photograph

of the stairs, No. 37.b., cut in the solid rock in the English cemetery, we

know that this was covered up with about 40 feet of rubbish; and there can

be little doubt but the scarped rocks visible in the cemetery itself extend

to a great depth below, and probably formed the southern boundary of the

ancient city.

Again it was found that there was not

less than 40 feet of rubbish in the branch of the valley of the

Cheesemongers near the citadel; there is also a large accumulation in that

small valley which has been described as joining the valley of the Kedron at

St. Stephen's gate.

In fact, we know that it was part of

the settled policy of the conquerors of the city to oblite-rate, as far as

possible, those features on which the strength of the upper city and the

Temple mainly depended. The natural accumulation of rubbish for the last

3,000 years has further contributed to obliterate to a great extent the

natural features of the ground within the city.

PLAN OF THE CITY

Having described the ground upon which

the city stands, we may now give a brief description of the city itself.

The form of the city may be described

as that of an irregular rhomb or lozenge, the longest diagonal of which runs

from NE to SW, and is 4,795 feet, or less than a mile long.

The northern side is 3,930 feet long,

the eastern 2,754 feet, the southern 3,245 feet, and the western 2,086 feet

long, as measured straight from point to point.

The total area of the city within the

walls is 209.5 acres, or one-third of a square mile, but in addition to the

large area of the Haram-es-Sherif, which is 35 acres, there are many open

places about the city walls which are not built upon.

It is consequently only equal in extent

to a very small English town, but the population is very dense, the houses

being piled upon one another, even in many places across the streets, and in

the year 1865 was estimated at about 16,000, but at Easter time the number

of pilgrims and travellers increase the population to about 30,000.

The whole city occupies no larger a

space than the block of the City of London included between Oxford Street

and Piccadilly, and between Park Lane and Bond Street.

There are five gates to the city, the

Damascus gate in the centre of the northern side, St. Stephen's gate on the

east side, a little to the north of the Haram enclosure. In the south side

there are two, the Water or Dung gate in the Tyropean valley, and the Zion

gate on the hill of that name.

Jaffa gate is in the centre of the west

side, and immediately under the walls of the northern front of the citadel.

The photographs, Nos. 32, 33, represent

the Damascus gate, and portions of the wall to the west of it, with the

scarped rocks upon which the wall is built. No. 34 represents the Zion gate.

The city is intersected from north to

south by its principal street, which is three-fifths of a mile long, and

runs from the Damascus gate to Zion gate. It is about the length of the

street running from St. James's Palace along Pall Mall to St. Martin's

Church. From this principal street, the others, with the exception of that

from the Damascus gate to the Tyropean valley, generally run east and west,

at right angles to it; amongst these is the Via Dolorosa along the north of

the Haram, in which is the Roman archway, called Ecce Homo. See Phot. No. 27

b.

THE QUARTERS OF THE CITY

The city is divided into quarters,

which are occupied by the different religious sects. The boundaries of these

quarters are defined by the intersection of the principal street, and that

which crosses it at right angles from the Jaffa gate to the gate of the

Haram, called Bab as Silsile, or gate of the Chain.

The Christians occupy the western half

of the city, the northern portion of which is called the Christian quarter,

and contains the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; the southern portion is the

Armenian quarter, having the Citadel at its northwest angle.

The Mahometan quarter occupies the

north-east portion of the city, and includes the Haram-es-Sherif. The Jewish

quarter is on the south, between the Armenian quarter and the Haram.

WATER SUPPLY

The city is at present supplied with

water principally from the numerous cisterns under the houses in the city,

in which the rain water is collected, but as even the water which, during

the rains from December to March, runs through the filthy streets is also

collected in some of these cisterns, the quality of the water may be well

imagined, and can only be drunk with safety after it is filtered and freed

from the numerous worms and insects which are bred in it. A supply is also

obtained from Joab's Well, from whence it is brought in goat skins on

donkeys, sold to the inhabitants; but this is also very impure.

Of the drainage of the city it is

sufficient to say, that there is none in our acceptation of the word, for

there are no drains of any kind from the city, and the accumulation of filth

of every description in the streets is most disgraceful to the authorities.

ANCIENT SUPPLY

But when we come to examine the ancient

systems for supplying the city with abundance of pure water, we are struck

with admiration for we see the remains of works which, for boldness in

design and skill in execution, rival even the most approved system of modern

engineers, and which might, under a more enlightened government, be again

brought into use.

From the three Pools of Solomon, as

they are called, water was led by a conduit from the lower pool along the

contour of the ground into the city, the distance being about 13 miles, and

the fall 538 feet but the pools were supplied not only from the "sealed

fountain" immediately above them, but from a conduit which has been traced

for several miles along the Wady Urtas, but not to the source from which the

water was obtained. (This has since been traced by Capt. Wilson in a fine

fountain in the Wady Aroob, and the Pacha of Jerusalem has repaired the

conduit from Solomon's Pools to Jerusalem, which is now supplied from Ain

Etan and the "sealed fountain" above the upper pool).

Josephus tells us that " Pilate, the

procurator of Judea, undertook to bring a current of water to Jerusalem, and

did it with the sacred money, and derived the origin of the stream from the

distance of 200 furlongs" (Antiquities of the Jews, Book XVIII, Chap.

III. par. 2); and it is quite possible that this is the work referred to.

In constructing this conduit, tunnels

were cut through a hill near Bethlehem, and through another hill on its way

to the valley of Hinnom, crossing which, above the Lower Pool of Gihon, it

was led round the southern end of Mount Zion, and entered the city at the

altitude of 2,420 feet on the west side of the Tyropean valley.

The conduit was not traced beyond this;

but by reference to the levels within the city, it is evident that it might

have been carried as far up the Tyropean valley as the spot on which the

Austrian Hospice now stands, the level on the front of which is 2,418 feet,

but this is much above the original level of the ground. It might also have

been led to any of the cisterns within the Haram enclosure, the height of

the surface ground being only 2,418 feet at the northern gates. The Pool of

Bethesda might also have been filled from it, the height of the bottom of

which is 2344 feet.

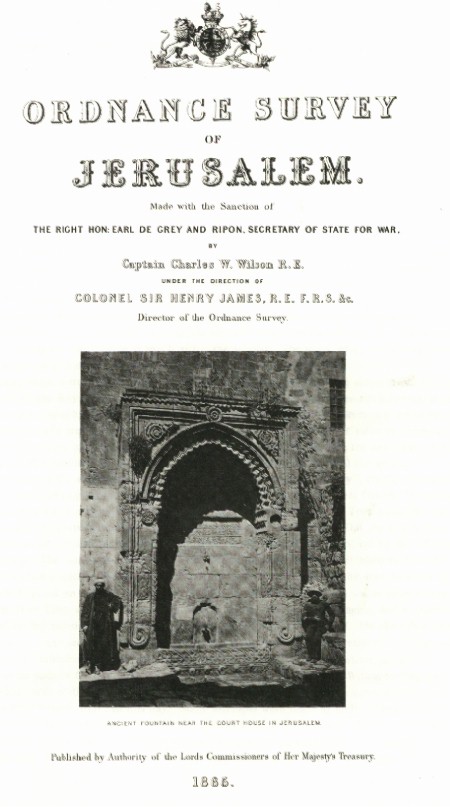

The two beautiful fountains in the

street El Wad, and that near the court-house, of which photographs are given

(see Frontispiece and No. 28 a.), might also have been supplied with water

brought in at the level of this conduit, these are supposed to be of the

sixteenth century, (Moryson, who was at Jerusalem in 1596, says, when

describing this part of the city, " Here I did see pleasant fountains of

waters.")

But there is a second conduit, which is

still more remarkable, and which we have distinguished by the name of the

high-level conduit. This comes front the south, down the Wady Byar, in which

it is probable a reservoir was formerly constructed; a tunnel through a hill

led round the Upper Pool of Solomon at an elevation of 2,616 feet, and

preserving its elevation by following the contour of the ground, till it

crosses the ridge of the hill to the west of Bethlehem; it is carried by a

syphon across a hollow which lies in its course, near Rachael's tomb, the

lowest part of the syphon being over 100 feet below its mouths.

This syphon is made of blocks of stone

with collar and socket joints, and covered with rough rubble in cement to

strengthen and protect it, as shown in the sketch. The internal diameter of

the syphon is 15 inches.

His Royal Highness Prince Arthur

examined a stone syphon of a similar kind at Patara, in Lysia, at the

south-west angle of Asia Minor, the internal diameter of which was nine

inches.

This high level conduit then crosses

the plain of Rephaim towards Jerusalem, and most probably passed round the

Upper Pool of Gihon and entered the city through the citadel; the fall from

above the Pools of Solomon to the Jaffa gate being 88 feet.

It will thus be seen that the water by

these conduits was brought from different sources; and that by the high

level one the upper city could be fully supplied with water, and that means

were provided for running the water of the upper into the lower both at the

Pools of Solomon and at the Pools of Gihon. This arrangement seems to prove

that the city was supplied at one and the same time from two principal

sources, as well as from the sealed fountain above the Pools of Solomon.

As regards the tradition that the city

was supplied from springs within its walls, the geological and physical

structure of the ground, taken in connexion with these great works to supply

the city from distant sources, renders it extremely improbable that any

spring of importance ever existed within the city walls. The valleys

surrounding the city are dry water-courses, such as may be seen in the chalk

districts of this country; and it is only during the heavy rains that the

surface water is in part carried off by them. The spring in the Tyropean

valley, with steps cut down to it, must necessarily have given only a very

insignificant quantity of water; and the quality and quantity of water found

at the Pool of Siloam, although described by Josephus as being sweet and in

great plenty, is now very impure and insignificant in quantity...

HOLY SEPULCHRE

...The Haram-es-Sherif is a

large quadrilateral enclosure of 35 acres, and nearly one mile in circuit,

The northern side being 1,042 feet

long,

the eastern, 1,530 feet,

the southern 922 feet,

the western 1,601 feet long.

The Mosque of Omar, or Dome of the

Rock, stands on a platform a little to the west of the centre of the

enclosure. The Dome of the Chain, or Tribunal of the Prophet David, is as

near as possible in the centre of the enclosure.

The Dome of the Rock is a magnificent

building, erected over and around the Sakhra. The Sakhra is a portion of the

natural rock, the summit of Mount Moriah; its highest point stands 4 feet

9.5 inches above the marble floor of the Mosque, and is 2,440 feet above the

level of the sea.

Beneath the Sakhra there is a cave,

which is entered by descending some steps on the south-east side. The cave

itself is about 9 feet high in the highest part, and 22 feet 6 inches

square; a hole has been cut through from the upper surface of the rock into

the chamber beneath, and there is a corresponding hole immediately under it,

which leads to a drain down to the valley of the Kedron. This hole is

supposed to have been made for the purpose of carrying off the blood of the

animals sacrificed on the rock when it was the altar of burnt offerings to

the Temple.

The Mahometans venerate this rock as

the spot from which, according to their belief, their prophet ascended to

heaven.

The Dome of the Rock, as we see it at

present, is a restoration by Soliman the Magnificent, iii the middle of the

sixteenth century, of the building originally erected over the Sakhra by Abd-el-

Melik-Ibn-Menvan in AD 688 to 691.

The Crusaders took Jerusalem in AD

1099, and called the Dome of the Rock the "Temple of the Lord," and the

mosque El Aksa the "Palace of Solomon;" and it was here that King Baldwin

founded the celebrated order of Knights Templars.

After the expulsion of the Christians

these buildings were again converted to the purposes for which they were

originally designed.

ENCLOSURE OF THE TEMPLE BY HEROD

As regards the question as to whether

the present area of the Haram-es-Sherif corresponds with the area of the

enclosure of the Temple, as it was built by Herod, we are informed by

Josephus that in the time of Herod "the fortified places about the city were

two, the one belonging to the city itself, the other belonging to the

Temple; and those who could get them into their hands had the whole nation

under their power, for without the command of them it was not possible to

offer the sacrifices;" and again, "Herod had now the city fortified by the

palace in which he lived, and by the Temple, which had a strong fortress by

it called Antonia, and was rebuilt by himself." The similarity of the

commanding positions selected for these two fortresses, the citadel and the

tower of Antonia, and of the ground forming the two hills, is very striking.

The fortress rebuilt by Herod was that

formerly built on the same spot and called Baris.

This fortress, Josephus goes on to say,

"was erected on a great precipice," and " stood at the junction of the

northern and western cloisters, that is, on the north-west angle of the

enclosure of the Temple;" and that "it had passages down to both cloisters,

through which the guard (for there always lay in the tower a Roman legion)

went several ways among the cloisters with their arms on the Jewish

festivals, in order to watch the people."

Josephus, in his description of the

siege of the Temple by Pompey, BC 63, says that the Roman Commander found it

impossible to attack it on any other quarter than the north, on account of

the frightful ravines on every other side; and that even on this side he had

to fill up "the fosse and "the whole of the ravine, which lay on the north

quarter of the Temple;" and in the description of the siege of the Temple by

Herod, BC 38, 37, he says, that Herod made the attacks in the same manner as

did Pompey, that is, from the north side of it.

When he comes to the description of the

siege by Titus, AD 70, the Temple with its enclosure, and the tower of

Antonia at the north-west angle of the enclosure, having been entirely

rebuilt by Herod, BC 17, Josephus says that the design of Titus was "to take

the Temple at the tower of Antonia;" and that for this purpose he raised

great banks; one of which was at the tower of Antonia, and the other at

about 20 cubits from it; and that for the purpose of obtaining materials for

filling up the immense fosse and ravine to the north of the Temple, he had

to bring them from a great distance; and that the country all round for a

distance of 19 or 12 miles was made perfectly bare in consequence.

After a protracted siege the tower was

at length taken possession of by the Romans, and from it Titus directed the

further operations of the siege against the inner enclosures of the Temple

itself; during which "the Romans burnt down the northern cloister entirely,

as far as the east cloister, "whose common angle joined to the valley that

was called Kedron, and was built over it; on which account the depth was

frightful."

Now, on referring to the plans and

photographs of the Haram enclosure, No. 7, we see that there is a high rock

on its north-western angle, the precipice upon which the tower of Antonia

formerly stood, and upon which the barracks for the Turkish guard now

stands; we see also that this rock has been in part cut away to make the

enclosure square, as Josephus tells us it was.

We see also that the northern side of

the enclosure extends to the edge of the valley of Kedron, and that outside

there is an immense fosse, now called the Pool of Bethesda, No. 16, and also

the ravine which has been described as being on the northern quarter of the

Temple.

It would seem, therefore, to be

impossible to resist the conclusion, that the northern front of the Haram is

identical in position with that of the northern front of the enclosure of

the Temple, as it was built by Herod, for the description would apply to no

other position for it.

In the description of the enclosure of

the Temple, Josephus tells us that "both the largeness of the square edifice

and its altitude were immense, and that the vastness of the stones in the

front was plainly visible;" and that "the wall was of itself the most

prodigious work that was ever heard of by man."

By means of the photographs and actual

measurements we can judge how far this description is applicable to the

lowest, and therefore oldest, courses of masonry, which can be traced at

intervals nearly all round the enclosure of the Haram.

In examining the photographs, Nos. 17

and 18, of the north-east angle, we find that the lower courses of the

masonry are composed of immense stones, one of which is no less than 23 feet

8 inches long and 4 feet deep; and that there is a wide "marginal draft,"

5.25 inches wide to these stones, giving the masonry a very bold, and at the

same time a very peculiar character, which should be specially noted.

The "batter," or slope of the wall, is

obtained by setting back each course of stones 4 or 5 inches, which also

gives a peculiar character to the masonry.

From the north-east angle we trace this

peculiar masonry down to, and for 51 feet beyond, the Golden Gate; and again

in great perfection for about 250 feet before arriving at the south-east

angle, No. 11, where we see the same peculiar marginal draft to the stones

and batter to the wall as at the north-east angle; one of the stones here is

39 feet 8 inches long. Turning the south-east angle, we trace the same

peculiar masonry nearly all along the southern side of the enclosure to the

south-west angle, Nos. 12, 13, where again this grand old masonry is seen in

great perfection, one of the stones at this angle measuring no less than 38

feet 9 inches in length, 19 feet deep, and 4 feet thick.

Thirty-nine feet north of the corner we

meet with the springing of a great arch, called Robinson's arch, No. 14.

This arch was 50 feet wide, and must have had a span of about 45 feet.

Proceeding northward, we trace this old

masonry at one of the ancient gates of the city, the whole of the lintel

over which could not be measured, but the part exposed measured 20 feet 1

inch in length, and was 6 feet 10 inches in depth. Immediately north of this

gate is the Wailing Place of the Jews, in which the old masonry is again

seen in great perfection, Nos. 14, 15.

From this the old wall is traced to the

pool or cistern " El Burak," under the entrance gate (Bab-as-Silsile) to the

Haram, the northern portion of which is covered by a semicircular arch,

having a span of 42 feet and a width of 43 feet. This arch was discovered by

Captain Wilson; it abuts against the old wall, and, as in Robinson's arch,

the springing stones form part of the old wall itself.

The western wall of the enclosure is

perfectly straight throughout its length, but from Wilson's arch northwards

the Haram wall can nowhere be seen below the level of the enclosure. There

is an accumulation here of rubbish to the depth of 72 feet, on which the

modern Moslem houses arc built too close together to admit of explorations

under ground, and which, if it were possible, would not be permitted by the

Turkish Effendis, the tombs of whose families are placed as close as

possible to the sacred enclosure.

We see, however, that all round the

enclosure, where it is possible to examine the wall, we have the same grand

old masonry; and as there can be no doubt but that Robinson's arch is part

of the bridge which Herod built across the Tyropean valley, and led to the

royal cloister, which he also built along the south side of the enclosure of

the Temple, it necessarily follows that the present Haram enclosure is

identical with the enclosure of the Temple of Herod.

We are further confirmed in this view

of the subject from the description which Josephus has given of the south

side of the enclosure, " which reached in length from the east valley unto

that on the west, for it was impossible it should reach any further;" and we

see how this side extends, as described, to the very edge of the valley on

each side, and this description would not apply to any other supposed

position or extent of the south side.

So again, if we examine the

substructures on this side, we see that in making the foundations some of

the inner parts, as Josephus says, were included and joined together as part

of the hill itself to the very top of it, when " he (Herod) wrought it all

into one outward surface, and filled up the hollow places which were about

the wall, and made it level on the external upper surface."

In the south-east angle we find that

the present level surface of the ground is supported by a great number of

arched vaults, and although the existing vaults may be of a much more recent

date than those constructed by Herod. it is difficult to resist the

conclusion that the supporting pillars are on the exact lines of the ancient

supports, the distances between them corresponding so nearly with the

dimensions given by Josephus, viz., 45 feet for the central walk, and 30

feet for the two others.

After a careful consideration of what

has been written about the sites of the Holy Places, I feel convinced that

the traditional sites are the true sites of Mount Zion and the Holy

Sepulchre, and of Mount Moriah and the Temple.

Ordnance Survey Office,

Southampton, 29th March 1866.

HENRY JAMES,

Colonel Royal Engineers

III. HARAM-ES-SHERIF

Haram-es-Sherif is the name now

commonly applied to the sacred enclosure of the Moslems at Jerusalem, which,

besides containing the buildings of the Dome of the Rock and Aksa, has

always been supposed to include within its area the site of the Jewish

Temple. Mejr-ed-din, as quoted by Williams, gives Mesjid-el-Aksa as the

correct name of the enclosure, but this is now exclusively applied to the

mosque proper.

The masonry of the wall which encloses

the Haram is of varied character, due to the numerous reconstructions which

have taken place during the present era. The lowest courses, and therefore

the oldest, are built of what have been generally called " beveled" stones,

a term which has led to much confusion, the style being in reality almost

identical with that of the granite work in the forts now building in

England, cache stone having a "draft" from one-quarter to three-eighths of

an inch deep, and two to five inches broad, chiseled round its margin, with

the face left rough, finely picked, or even chiseled, according to the taste

of the time or labour that could be spared upon it; of the rough work, some

portions of the wall near the south-east angle show the best specimens; of

the finer, the Wailing Place is a well-known and favourable example. The

annexed sketch shows the detail from stones at the Wailing Place; from local

indications the fine dressing appears to have been given to the faces after

the stones were set. Above these stones, and often mixed with them, are

those and during the first reconstruction, large blocks scarcely inferior in

size to the older ones, but having plain chiseled faces without a marginal

draft ; this gradually changes into another style, similar in workmanship,

but with a very marked difference in the size of the stone, and above comes

the later work, of the same date as the great rebuilding of the walls by

Suleiman the Magnificent. At the south-west corner another species of

masonry is found, which, from other remains of the same kind in the city,

appears to be of the Saracenic period, prior to the Crusades; the stones are

small, and have a deeply-chiseled draft round their margins, so as to leave

the faces projecting roughly two or three inches. The mode of obtaining the

necessary batter or slope to the wall has been in each style of building by

setting the courses back from half an inch to an inch) as seen in sketch.

It is extremely difficult to tell what

portion of the old masonry of the Haram wall is really "in situ;" it may be

urged that the stones are so large that they could not easily have been

over-thrown, and that wherever they are found in masses they must

necessarily be in their original position, but a strong argument against

this is the badness of the actual building, for it seems hardly conceivable

that men who went to such great expense and labour in tooling the beds and

sides of their stones should afterwards disfigure their work by leaving wide

open joints, as is here usually the case; some of this defect is due to

weathering, but the part thus destroyed can easily be seen, and at Hebron

and Baalbek, where the masonry has been less disturbed than at Jerusalem,

the joints are so close that it is difficult to insert a knife. Great want

of judgment has been shown in the choice of material, and no care has been

taken to place the stones on their quarry beds, which has made the progress

of decay much more rapid than it would otherwise have been. To the north of

Jerusalem, between the Tombs of the Judges and the village of Shafat, there

is a very curious tomb, having in its vestibule a representation of the old

mural masonry cut on the solid rock, and if this is a copy, as it probably

is, of the style in use when the tomb was made, there is certainly nothing

now "in situ" in the Haram wall, except perhaps the south-west corner and a

portion of the wall under the Mahkama. A glance at the accompanying sketch

will show the beautiful regularity of the work at the tomb, having, in

elevation, the appearance of Flemish bond in brickwork, the marginal drafts

of the blocks being chiseled and the faces finely picked. Though, however,

much of the masonry now visible may not be " in situ," the present wall has

probably been built on the foundations of the older one, and the same stones

re-used without that regard to neatness of workmanship which would be shown

in a time of great national prosperity.

The material used in the older portions

of the wall is from the "missae" and "malaki" beds of stone, in the later

Turkish additions from the "cakooli." The "missae," if well chosen, is

extremely hard and good, and may be readily recognized in the wall by the

sharpness of its angles, which are often as clean and perfect as when they

left the mason's hands, even the marks of the toothed chisel being seen on

many of the marginal drafts; this stone, however, varies in. different beds,

and little care has been shown in selecting the best, many of the fine

blocks being ruined by the rain or moisture which has found its way into the

faults or veins which run through them. The "malaki" is good if it can be

kept from the rain, and stone free from flaws is used; most of that in the

wall has suffered severe]y from the weather. The "cakooli" is soft; and

inferior as a building material.

A fuller description of the lower or

oldest portion of the wall, as seen from. the outside, may now be given,

commencing with the north-east angle, where, in the so-called Castle of

Antonia, we find five perfect courses of large stones with marginal drafts,

and above these at the northern end portions of six others; the draft is

here 5.5 inches wide, and the faces of the stones are better worked than

near the south-east angle; the courses vary from three to four feet in

height, and some of the blocks are of great length, one being 23 feet 8

inches. The straight joint left between this mass of masonry and the city

wall running north, with the sudden termination of the large stones, shows

it to have been in existence long before the latter was built, and the

appearance of the southern end, where the stones are properly bonded and the

draft completed round the corner, would seem to indicate that the four

lowest courses were "in situ," if it were not for the irregularity and

coarseness of the jointing. Between this tower and the Golden gateway, one,

two, three, and occasionally four courses of large stones are visible, the

lowest of which projects beyond the others, and seems never to have had the

dressing of its face completed. Several of the stones in this part of the

wall are the remains of door jambs and lintels.

The piers of the Golden gateway are

built of stones having plain chiseled faces; the northern one is not so well

built as the southern, and stones taken from other buildings seem to have

been made use of, if we may judge from one or two which have reveals or

notches cut in them. The piers are flanked by buttresses of more modern

date, which were built to sustain the mass of masonry placed above the

gateway when it was turned into one of the flanking towers of the wall, and

the entrance was probably closed at the same period; to gain the necessary

slope or batter the buttresses were pitched forward four inches, and to take

away the unsightliness of the projection the inner edges were chamfered, as

seen in sketch annexed.

From the Golden gateway to the

"so-called" postern, a distance of 51 feet, there are three courses of large

stones, with marginal drafts three to six inches wide, and extremely rough

faces, projecting in many cases as much as nine inches. Over the doorway

there is a sort of lintel, but there are no regular jambs, and the whole has

more the appearance of a hole broken through the masonry and afterwards

roughly filled up, than that of a postern in a city wall, still it probably

marks the site of Mejr-ed-din's gate of Burak. To the left or south of this

there is a curious stone, hollowed into the shape of a basin, which on three

sides is perforated by a round hole, and attached to the one at the back is

a portion of an earthenware pipe, which was probably at one time in

connexion with the water system of the Haram, and supplied a fountain at

this place.

Southwards from the postern the stones

have all plain chiseled faces, and portions of several broken marble columns

have been built transversely into the wall, with their ends left projecting

several inches, but shortly after passing "Mahomet's pillar" the marginal

draft is again met with, and the ground falling rapidly towards the

south-east angle, exposes 14 courses at that point. Shortly before reaching

the offset which mark the position of the corner tower, two stones, forming

the springing of an arch, and extending over a length of 18 feet, are seen,

and immediately above them there has been at some period a window to admit

light to the vaults within, which is now closed with modern masonry, leaving

a small chamber in the thickness of the wall. The annexed sketch shows the

arrangement of the stones, which do not appear to be "in situ," and have

nothing in their appearance to justify the belief that they formed part of

the arch of a bridge over the Kedron valley; it seems more probable that

they came from the ruins of the tower close by, part of the original

vaulting of which, made of large stones, may still be seen in the "Cradle of

Jesus."

The stones at the south-east angle form

a species of ashlar facing to a mass of coarse rubble work (seen in the

vaults), and from this and the fact that the offset at the north end is

sometimes formed by notching out the stone, the draft being continued on

both tower and wall, it seems probable that they are in their original

position. The courses vary in height from 3 feet 6 inches to 4 feet 4

inches, and are set back from half to three-quarters of an inch as they

rise; the upper portion of the wall is sadly out of repair, and looks as if

the least touch would bring it down; from its summit the wavy, irregular

course of the eastern boundary of the Haram can easily be distinguished by

the eye.

Turning the corner and proceeding along

the southern wall, the 14 courses of large stones break down rapidly, and

the ground rises so as to allow only one course to be seen at the "single

gateway," a closed entrance to the vaults, which has a pointed arch.

Between the "single" and "triple

gateways" there is one course of stones with the marginal draft, with a few

scattered blocks above. The " triple gateway" is closed with small masonry,

its arches are semicircular, with a span of 13 feet, and the stones in both

piers and arches have plain chiseled faces. In front of the gateway are some

large fiat slabs of stone, which appear to have formed part of a flight of

steps leading up to it; an excavation was made here, and three passages

discovered by Monsr. De Saulcy explored, a description of which will be

given in another place. To the west of the gateway there are two courses of

stones with the draft, and one of these can be traced to the " double

gateway," where it abruptly terminates; this course is of some height, 5

feet 5 inches being seen above ground, and the blocks are finely finished

with plain picked faces, and 3.25 inch draft chiseled round the margins; one

of these stones, which forms part of the left jamb of the western entrance

of the "triple gateway," has a moulding worked on it, which seems to have

been intended as a sort of architrave, and to have been worked at the time

the gateway was built, certainly after the stone was set; on its face the

characters shown in Sketch 4, Plate XI can be traced.

At the "double gateway," a portion only

(5 feet 8 inches) of which is seen, further progress is stopped by a wall

running southwards; but, entering the city, part of the ornamental arch over

the western door is found in a vault of the Khatuniyeh, and thence the

southern boundary of the Haram may be traced to the south-west angle. The

construction of the "double gateway" will be better examined from the

interior; but here it may be noticed that adjoining the relieving arch over

the lintel of the eastern door is the Antonine inscription built into the

wall upside down, most of the letters still retain their sharpness, and with

the aid of a magnifying glass may be read from the photograph; they are

shown in Sketch 5, Plate XI.

In the portion of Haram wall seen

within the vaults of the Khatuniyeh plain chiseled stones and those with a

marginal draft are mixed up together, but from thence to 50 feet east of the

corner the former only are found; at this point, by forcing a way through

the thick growth of cactus, the junction of the two styles of masonry may be

seen, and as this takes place near the ground line, it shows how complete

must have been the destruction of this part of the retaining wall at the

period of reconstruction. The south-west angle, and 50 feet on either side

of it, is the finest and best preserved piece of old masonry in the wall,

and the stones have more the appearance of being "in situ" here than at

other places; one of the blocks is 38 feet 9 inches long, nearly 4 feet

thick, and 10 feet deep, and there are others of little less size; the

bonding of the stones has been carefully attended to, and the workmanship is

admirable; unfortunately the accumulation of rubbish and cactus against the

sides of the wall prevent its being seen to such advantage as the south-east

angle, which) however, is greatly its inferior in construction and finish.

The southern boundary of the Haram is a straight line, the south-west corner

a right angle, and the south-east corner an angle of 92 degrees 50 minutes;

some trouble was experienced in getting the exact line of the southern wall,

on account of the buildings which are clustered against it beneath the

Mesjid-el-Aksa.

Thirty-nine feet north of the corner is

the springing of an old arch, first brought to notice by Dr. Robinson, and

now known by his name; portions of the three lower courses still remain, and

from the appearance and position of the stones there can be no doubt about

their having formed part of the original wall; the breadth of the arch is

exactly 50 feet, and its span must have been about 45 feet, but from the

upper stones having slightly slipped, and their surface being a good deal

weather-worn, it was not possible to determine the exact curve; indeed, in

several of the stones the line of the curve is no longer to be

distinguished, as they have been taken from the "malaki" bed, which is soft

and easily acted upon by. the weather. An excavation was carried to a depth

of 37 feet, in search of one of the piers, without much result, except to

impress still more on the mind the magnificent effect which must have been

produced by a solid mass of masonry rising sharply from the valley to a

height of probably not less than 80 or 90 feet, and crowned by the cloisters

of the Temple. The line of springing of the arch is on a level or nearly so

with the present surface of the ground, and an offset of 1 foot 3 inches,

forming the top of the eastern pier or buttress, can just be seen.

From the arch to Abu Seud's house, and

in his house as far as could be seen, there is a mixture of plain chiseled

stones and those with a marginal draft, but just beyond this, in a small

yard to the south of the Wailing Place, the older masonry is again found in

the shape of an enormous lintel which S covers a doorway, now closed,

leading into the small mosque dedicated to El Burak, the mysterious charger

of Mahomet. The masonry is here of good, well-chosen material, and

apparently "in situ;" the whole of the lintel could not be seen, its

measured parts were 20 feet 1 inch in length by '6 feet 10 inches in height.

At Abu Seud's house is the

Bab-al-Magharibe, or Gate of the Western Africans, so called from its

proximity to the mosque of the same name; the approach to it is by a steep

ascent from the valley, and it enters the Haram on a level with the area;

there is nothing of great antiquity in its character.

Immediately north of the lintel is the

Wailing Place, which has always been considered as part of the original

sustaining wall of the Temple area, but the carelessness of the building,

and the frequent occurrence of coarse open joints makes it doubtful whether

the stones really are "in situ." The chiseled draft is here from 2 to 4

inches broad, and from one-quarter to three-eighths of an inch deep, and the

faces are all finely worked. Many of the stones are a good deal worn by the

weather, the decay being hastened by their not being placed on their quarry

bed, or by their softness; indeed the material used is of very different

quality, some being of the best "missae," as the whole of the second course

from the bottom; which is admirably finished and in a good state of

preservation, but above and below this, besides a few blocks of "malaki," a

great deal of the upper " missae" has been used; this stratum, which may be

almost called "cakooli," contains. a number of small nodules, which become

loosened by moisture, and commence the work of destruction. The photograph,

"Detail of Masonry at Wailing Place," shows the different kinds of stone

used, and a few of the blocks set on edge. Several holes cut in the surface

of the wall were rather puzzling, till their use was discovered, whilst

exploring the vaults under the Mahkama, where they receive the groin point

of the arches, so that a series of similar vaults must at one time have

covered a great portion of the Walling Place wall.

Entering a small garden at the north

end of the Wailing Place, a continuation of the same style of masonry is

seen, and can be traced at intervals in the vaults under the Mahkama till

the edge of the pool or cistern of " El Burak" is reached.

From this garden the face of the

Mahkama, or court house, also built of stones with marginal drafts, can be

examined; it is evidently constructed from old material, and at a much later

date than the Haram wall, yet some of it has more the appearance of being "

in situ" than many of the other remains in the city. The double series of

vaults which support the court house seem of different ages, from the

mixture of segmental and pointed arches; in those next the Haram, the

skewbacks of the arches, and where requisite, the seat of the groin, has

been cut out of the wall itself.

Descending into the pool of "El Burak,"

we find a fine portion of the Haram wall exposed, for a length of 36 feet,

and then reach the springing of a large arch covering the pool. This arch is

semi-circular, has a width of 43 feet and a span of 42 feet, abutting,

westwards, on a solid mass of masonry' of the same style as the Haram wall

There are 23 courses in the arch of equal thickness, which gives an almost

painful appearance of regularity; and the stones, as far as could be judged

from the bottom, ranged from 7 to 13 feet in length, not equal in size to

those near the south-west angle, but from their perfect state of

preservation forming the most remarkable remain in Jerusalem. Here, as at

the south-west angle, the stones at the springing and for two courses above

form part of the Haram wall, and whatever date is given to the masonry of

the Wailing Place must be ascribed to this, whether it be the Herodian

period or that of the first reconstruction after the taking of the city by

Titus; if of the former, its perfect preservation may be easily understood,

by its forming the best and readiest means of communication for troops

passing from one hill to the other, and, as such, of the greatest importance

to the Roman garrison.

Immediately north of this arch is

another, which covers the remainder of the pool; it is of a perfectly

different character, being made of rubble work of small stones, and not

having such a large span; it appears also to be slightly pointed, but this

cannot be very well seen from the bottom of the pool. At this point also

there is an offset of five feet forming the abutment of the later arch, and

built of rubble, which conceals the true line of the Haram wall. The north

end of the pool is closed, and there is a flight of steps leading up to a

door in it filled with loose masonry; an attempt was made to break through

this and get down to the Haram wall 6n the other side, but unfortunately

without success. Within the pool the joints of the large stones are covered

with cement, and the sides of the later masonry at the south end are

completely coated, but it is of bad quality, and beginning to peel off. The

floor is formed of two thick layers of good cement eighteen inches apart,

the space between being filled with rubbish, and the lower layer resting on

a bed of small rubbish levelled to receive it. Through one of the arch

stones a hole has been broken to draw water, but the pool seems to have been

dry for some years. This is probably "the bridge" mentioned in the Norman

Chronicle as quoted by Williams, at which time there appears to have been a

free passage beneath to the "Dung Gate."

The principal entrance to the Haram

area passes over the arch and enters on a level with the ground within

through a double gateway; the one on the right is called the Bab-as-Silsile

(Gate of the Chain), and the one on the left the Bab-as-Salam (Gate of

Peace); at the bottom of the left jamb of the latter there is a massive

stone with marginal draft, the north end of which corresponds with the end

of the arch over the pool below. The decoration of the exterior face of the

gateway is very handsome, and some of the twisted columns have been used in

its construction.

From this point to the north-west angle

the Haram wall can nowhere be seen below the present level of the area,

attempts were made to get at it underground through every opening that could

be found, but they were all unsuccessful; there is, however, one place which

was not noticed till the winter rains had set in and stopped exploration,

where something might be discovered; viz., a large cistern, near the

Bab-an-Nazir, in the court yard round which the houses of poor Moslem

pilgrims are ranged. North of the. Bab-as-Salam the rubbish along the

western wall rises nearly to the level of the Haram area, and close to the

Bab-al-Kattaanin has a depth of 72 feet; on this, and closely clinging to

the western cloisters of the enclosure, are the modern Moslem houses, built

too closely together to allow of exploration or excavation, if this were not

already prevented by the numerous tombs of Turkish effendis placed as near

as possible to the sacred enclosure, and reverenced by the present

generation as of equal if not greater sanctity than the area itself.

There are six gates on the western side

north of the Bab-as-Salam, known as the Bab-al-Matbara (Gate of the Bath),

the Bab-al-Kattanin (Gate of the Cotton Sellers), the Bab-al-Hadid (Iron

Gate), the Bab-an -Nazir or Nadhir (Gate of the Inspector), also known

amongst Moslems as the Bab Ali-ad-din-al-Bosri, the Bab-as-Sarai (Gate of

the Seraglio), and the Bab-al-Ghawanime, or Ghawrine, called also the

Bab-al-Dawidar (Gate of the Secretary). The first of these is a small gate

formerly leading to the Hammam-es-Shefa but now to the latrines attached to

the Haram; the second is a handsome Saracenic doorway opening into an

arcade, along the sides of which are ranged a series of vaulted chambers,

once the Cotton Bazaar, now the receptacle of all the filth of the

neighbourhood which is carelessly thrown in and walled lip when a chamber

becomes full to overflowing. In the court yard of an effendi's house between

the Bab-al-Hadid and Bab-an-Nazir, a portion of the exterior face of the

Haram wall can be seen; its direction is in the exact prolongation of the

hue of the Wailing Place, and the wall is composed of large blocks (with

plain chiseled faces), backed with coarse rubble, one or two of the stones

have the marginal draft, but the style of the work is that of the middle

portion of the Wailing Place wall, and it is apparently of the same date.

Great hopes were entertained of finding a lower portion of the wall in a

cistern at this place, but on descending, the cistern turned out to be a

small modern one built in the rubbish and not reaching as far as the wall;

the effendi said that in sinking for the foundations of his house, he went

down between 30 and 40 feet, and then finding no bottom built on the

rubbish, and so great was his fear of it falling down from any disturbance

of the ground in the neighbourhood, that not even the offer of a large

bakhshish could induce him to allow a small excavation in front of the Haram

wall so as to determine the character of the lower masonry. The Bab-as-Sarai

leads to the official residence of the Pacha of Jerusalem, and is the gate

by which Frank visitors generally enter the Mosque grounds. The

Bab-al-Ghawanime is near the north-west angle, and is partly formed by

cutting through the natural rock which here rises to the surface. The

boundary of the Haram at the north-west angle is formed by houses built on

the rock, which has been scarped on the side facing the area.

Turning the corner and proceeding along

the northern side, the Barracks form the boundary for some distance; they

are built on the rock, somewhat in the manner shown in the annexed sketch,

the main building, which is entered by a flight of steps, being above the

natural level of the ground; the escarpment on the south side is in places

23 feet high, and can be seen from the interior of the Haram , that on the

north side is found in a chamber entered from the Tarik Bab Sitti Maryam

(Via Dolorosa), by a door near the Barrack steps; the scarped face is 10

feet in from the street, and rises to a height of 8 feet, how far it

continues below the made-up floor of the vault cannot he seen without

excavation. Between this and the Birket Israel (Pool of Bethesda) the ground

is so covered with buildings standing on a level with the Haram area, that

neither rock nor wall can be traced, but in the pool the northern retaining

wall is exposed to some depth below the Haram level; it is quite different

in character from any other portion of the wall, and its construction is

that ordinarily adopted in the pools round Jerusalem ; viz., large stones

set widely apart, the joints being packed with small angular stones, to give

the cement a better hold. In places large fragments of cement still adhere

to the wall, but the pool is useless as a reservoir; it now receives the

drainage of the neighbourhood, and the bottom is covered by a large

accumulation of rubbish which conceals the original depth and makes

exploration neither easy nor pleasant. At the west end there are two

parallel passages covered with slightly pointed arches and of considerable

size but now nearly choked up with filth, the drainage and refuse from the

houses above being discharged into them by holes broken through the crowns

of the arches ; near the pool there is a communication between the two

passages by a low arched opening, but the most curious feature is that both

passages are cemented as if they had been at one time used as water channels

or additional reservoirs, the southern one, which runs along the Haram wall,

was traced for 100 feet when the rubbish rose to the crown of the arch and

prevented further progress; the cement and rubbish unfortunately concealed

the character of the wall. The Birket Israel lies at the end of the shallow

valley, which running down from the north-west passes between the Church of

St. Anne and Al-Mamuniye, but it is difficult to say what was the original

character of the ground, and what portion of the pool is cut out of the rock

which is visible neither in the pool itself nor in the Haram behind it. The

eastern end is closed by a dam formed, of the roadway leading into the Haram,

and the city wall, but here again there is nothing to indicate the date or

mode of construction, and without excavation no one can be certain whether

the dam was built wholly or only in part at the time of the reconstruction

of the walls, or whether it is wholly artificial closing up the end of the

valley mentioned above, or partly rock and partly masonry. The annexed

section through the pool and wall shows the present nature of the ground

which deserves a more perfect examination. There are three entrances to the

Haram on the north side, the Bab-al-'Atm. (Gate of Obscurity), the Bab Hytta

(Gate of Pardon), which, according to Mejir-ed-din, derives its name from.

the command given by God to the Israelites to say "pardon" as they entered

it; and the Bab-al-Asbat (Gate of the Tribes [of Israel]), which is close to

the north-east angle, and so-called Castle of Antonia; the stones in the

north face of the castle have the marginal draft, and some of them appear to

be "in situ," but the greater portion is a reconstruction most probably of

the same date as the towers at the Damascus Gate; it is, however, much older

than the wall running northwards which joins on to it with a straight joint.

The area of the Haram is a curious

mixture of rock, made ground, and rubbish; in the north-west angle the rock

forms the surface over a considerable extent of ground, and at the

Bab-al-Ghawanime and under the Barracks there is an escarpment which rises

in one place to a height of 23 feet; a portion of the passage leading out

from the Bab-al-Ghawanime is cut out of the rock, and from this point the

bare rock is seen sloping gradually down to the north-west corner of the

platform, on which the Kubbat-as-Sakhra stands, where it again rises to

nearly the height of the platform pavement. The ground has been lowered by

cutting down perpendicularly at the north-west angle, and then removing the

overlying strata as far as the platform, so that the surface of the rock,

where seen, is at its natural slope or dip. Some very curious cuttings in

the rock, which had the appearance of small water channels, for supplying a

fountain, were noticed here but their arrangement and object could not be

clearly traced. The strata that have been removed are the upper thin beds of

"missae" and are exposed in section under the Barracks; they have a dip of

100 towards the east in the direction of the north wall, and of 150 towards

the south in the direction of the west wail. In the north-east corner and

between the Birket Israel and Golden Gate, there has been an immense amount

of filling in to bring this portion up to the general level of the area, and

it appears to have been done at a period long after the erection of the

Golden Gate, the north side of which is nearly hidden by an accumulation of

rubbish rising 26 feet above the sill of the western doorway. Immediately in

front (west) of the Golden Gate there is a deep hollow, the descent to the

entrance being over a sloping heap of rubbish, which, on excavation, would

probably be found to cover a flight of steps leading up to the higher level;

the southern side is not so completely covered as the northern, but even

here the rubbish is 9 feet above the western door sill, and soon rises to

the general level. A little to the south-west of the Golden Gate the rock is

again found on the surface, having a dip of 100 due cast, and here only one

layer of "missae" covers the "malaki," in which the cisterns are excavated ;

nearly opposite this a portion of rock "missae" is seen in the wall of the

platform. The south-east corner of the area is supported by an extensive

system of vaulting, a detailed account of which will be given in another

place. Over the space covered by the Masjed-al-Aksa and between it and the

platform there is much less rubbish than has generally been supposed; the

irregularity of the ground seems to have been levelled by building up the

southern part with massive masonry and filling in the inequalities; at one

point only, near the south-east corner of the platform, the natural rock is

seen, rising about 9 inches above the ground, and having its surface

chiseled so as to be horizontal, and near this there are a number of large

flat stones, probably the remains of some ancient pavement. Along the whole

western side of the area nothing can be seen sufficient to decide the

original character of the ground; the Mosque "Al-Burak" near the Magharibe

Gate, lies at a low level, but there seems no reason to suppose that there

are any more vaults in connexion with it, spite of the Moslem tradition,

which is here probably as groundless as it was proved to be in other places.

In the south-west corner are two or three cisterns, which, as far as could

be judged from the surface, appeared to be small and cut in the rock; if so,

it would go far to prove the non-existence of a system of vaults similar to

that at the south-east corner. There is nothing ancient in the appearance of

the masonry of the platform, and the covering arches of the vaults on the

west side and at the south-west corner are pointed; the chambers were so

covered with plaster that no rock could be seen, they appeared to have been

built to overcome the irregularity of the surface. At the north-west corner

the rock rises nearly to the level of the platform, and wherever it can be

seen in cisterns it is not far below the surface. The principal interest of

the platform centres in the rock covered by the Mosque, which gives it an

air of mystery and a prominence which, were the ground restored to its

original shape, it would not possess; in forming the platform, there is no

doubt that the rock was cut away in many places, and every possible means

taken to give a complete and conspicuous isolation to the central point.

The "Kubbat-as-Sakhra" (Dome of the

Rock), has been so frequently repaired and covered by various decorations,

that it is difficult to say what belongs to the original building, however,

westerly gales outside and Turkish carelessness within are rapidly reducing

the Mosque to its original state; no attempt has been made of late years to

carry out any repairs, and each succeeding winter sees the fall of larger

portions of marble, fayence, and mosaic work, which are carefully collected

and locked up till Allah shall send money to put them in their place again,

or what is more probable till they disappear through bolts and locks by the

mysterious agency of western "bakhshish." The rock is covered by a very

elegantly shaped dome, supported on four piers, standing in the

circumference of a circle of 75 feet diameter; between each of the piers are

three columns from the capitals of which spring slightly elliptical arches

which assist in carrying the tambour of the dome. This circle is surrounded

by an octagonal screen containing eight piers and sixteen columns which

carry an entablature above which are discharging arches slightly elliptical

in shape. There is a peculiar feature in the entablature of the screen, that

over the intercolumnar spaces the architrave is entirely omitted, and over

the columns is represented by a square block cased with marble. A slab from

one of the blocks had fallen, but on getting up to it nothing could be seen

except the mortar backing against which the slab had rested, and any

disturbance of this the Mosque attendants would not allow. The columns,

averaging 5 feet 11 inches in circumference for the screen, and 7 feet 10

inches for the inner circle, are of various coloured marbles, and

serpentine; they may have been taken from the remains of former buildings,

but this can hardly be the case with the capitals, which are all identical

in character and very similar to those in the basilica at Bethlehem, the

details of capital and entablature are well given by De Vogue, in "Le Temple

de Jerusalem," but after close examination no trace could be found of the

cross shown in his engraving, many of the monograms or bosses are quite

perfect, and have nothing of the cross about them, and in those destroyed

the obliteration is so complete that it requires a very vivid imagination to

make anything out of them.

Outside the screen is the main

building, also octagonal, composed of the best "malaki" stone, finely

chiseled, with close beds and joints, and-having on each side seven recessed

spices or bays with plain semicircular heads. There are four entrances to

the Mosque, the Bab-al-Tanne (Gate of Paradise), the Bab-al-Gharby (Western

Gate), the Bab al-Kible (Gate of the Kible, that is "the gate on the side

towards which they turn when praying," the Mecca side), and the

Bab-an-Neby-Daud (Gate of the Prophet David); each appears formerly to have

had an open porch of columns which with the exception of the one at the

Bab-al-Kible have been closed in and cased with marble, leaving just room

enough to enter by the doors, the side portions being turned into rooms for

the attendants of the Mosque.

As far as can be judged, the oldest

portion of the Mosque consists of the main building, screen, inner circle,

and discharging arches, in fact, everything below the tambour of the dome

stripped of its marble casing, ornament and roof, and this from the

regularity of its construction, and the perfect agreement of its details,

must have formed part of the original building.

The exterior of the Mosque is richly

decorated with marble and fayence. The casing of various colored marble

reaches from the ground to nearly the foot of the windows some little of it

may be original, but the greater portion is a patchwork, in which old

material has been used up, not, however, without some attention being paid

to the design which is generally chaste and simple. The slabs are fastened

to the stone by metal cramps, run in with lead, a good even bed of mortar

having been prepared to receive them as shown in annexed plan and section.

At the foot of the casing on the eastern side of the Mosque and built

without any regularity of design are some curiously sculptured marble slabs

evidently taken from some other building, as they have been cut down to fit

the height of the base or plinth of the Dome of the Rock, one of these slabs

was found forming part of the decoration of the Mihrab of John and

Zechariah, in Al-Aksa, and another, the most interesting, with a Greek

inscription partly cut off; built into the lower part of the casing within

the Dome of the Rock and close to the Bab-al-Gharby. The inscription is

given below, the latter portion of it seems to be "soterias Marias" in the

face of the slab is a simple wreath, similar to the one on Sketch 4, Plate

XIII, but without the intersecting squares in the centre. It seems very

probable that all these slabs were taken from some Byzantine Church, and

that the inscriptions were cut off when the material was re-appropriated;

nothing like them was found in any other part of the city. Above the marble

casing the original appearance of the Mosque has been altered by building

new windows with pointed heads into the old ones, and so badly has this been

done, without bond or tie of any kind, that some have completely fallen out,

and all those on the western sides are rapidly approaching the same fate,

leaving the semicircular arches behind plainly exposed to view. The whole of

this portion as well as the outside of the tambour was covered with fayence,

the eastern sides are perfect, and afford a good specimen of this style of

decoration, but in consequence of the prevailing westerly winds and rain the

sides facing that quarter are sadly out of repair. Three periods of

workmanship can be traced, of which the first and oldest is far superior to

the others both in elegance of design and quality of manufacture; the second

is also very good, and specimens of it may be seen in two or three places in

the city, where, in the Armenian church of St. James, it shows to better

advantage than when beside the finer work on the Mosque; the third period is

that of the later repairs which have been made in bad taste and with worse

material. Each piece of fayence is 9.5 inches square, and was bedded firmly

in strong mortar, a thick coating of which was spread over the whole

exterior surface of the building. The interior face of the external wall is

covered with a marble casing in which the use of old material is perhaps

more apparent than in the work outside; the piers of the screen and inner

circle are ornamented in the same way, and the soffits of the discharging

arches under the dome are covered with alternate slabs of black and white

marble. The capitals are gilded and the entablature painted with bright

colors to bring out the salient points in the architecture; the bottom of

the enablature is covered with a beautiful representation in bronze of vines

with clusters of grapes. The pavement of the mosque between the external

wall and screen is a confused mass of old material, amongst which there are

many portions of sculptured slabs like those seen outside, one of which, a

little to the north of the western gate is nearly perfect; between the

screen and inner circle the paving has been better cared for, and round the

rock itself the workmanship leaves nothing to be wished for.

The space between the external wall and

inner circle is covered by a flat roof with a paneled wooden ceiling, very

well finished, and similar to, though in a much better state of preservation

than, the ceilings in some of the old mosques at Cairo. The whole internal